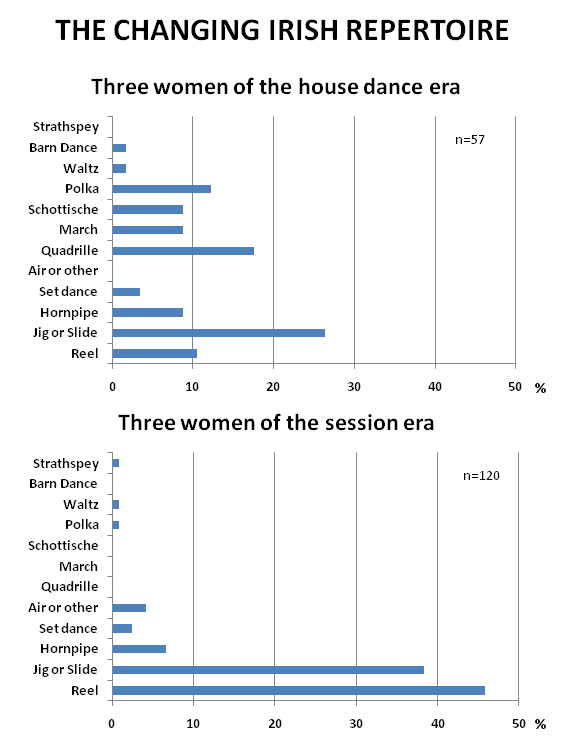

If we look at the sum total of the recorded legacy of three Irish women who played the concertina in the house dance era and compare it with the recorded legacy to date of three modern Irish women who play the concertina, a stark contrast emerges. The graphs below show a count of tunes by dance type for these three old time players:

Mary Ann Carolan (1902-1985), who played for house dances in The Hill of Rath in rural County Louth in the second decade of the twentieth century, and then stopped playing for over sixty years; Ella Mae O'Dwyer (1906-1992), who played for house dances in her youth and later for dances at her family's dance hall in rural Ardgroom, County Cork in the early twentieth century; and Katey Hourican (ca.1890-ca.1990) of Lough Gowna, County Cavan, of whom little is known, but who was of the same generation as the previous two women.![]() 45

45

Together, these women left recordings of 57 tunes, all made in the middle to late twentieth century. As young women, they played in the last decades of the house dance era, well before the House Dance Act of 1935. All played the German concertina.

A second part of the graph shows a count of tune types by dance for the current repertoire of three well known modern Irish women who play the concertina. Claire Keville, of Claran, County Galway; Edel Fox of Miltown Malbay, County Clare; and Dympna O'Sullivan of Lissycasey, County Clare were all born in the late twentieth century, nearly a century after the earlier three women listed above. All play the Anglo concertina. Each has issued either one or two CDs in the first decade of the twenty-first century. A total of 120 recorded tunes were counted from these recordings.![]() 46 Of course, neither graph captures the entirety of the repertoires of any of these six women, but perhaps it captures the general essence of the music they mostly preferred/prefer to play.

46 Of course, neither graph captures the entirety of the repertoires of any of these six women, but perhaps it captures the general essence of the music they mostly preferred/prefer to play.

Top: the recorded repertoire of three women concertina players of the house dance era,

by dance type: Mary Ann Carolan, Ella Mae O'Dwyer, and Katey Hourican.

Bottom: the recorded repertoire (CDs to date) for three modern day women concertina players.

Dance types are shown by percentage. The chart shows that the house dance favorites

(schottisches, quadrilles, polkas, waltzes) of the early players are absent in the repertoires of

modern players, to an extent not seen in the traditional music of the other three countries studied.

The differences are very clear. Over the past 80 years or more there has been a great narrowing of focus in the repertoire of Irish musicians - especially concertina players. This change in repertoire favors the step dance music of largely pre-Famine origin (primarily reels and jigs) to the near-exclusion of the many dances of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century house dance era: quadrille tunes, schottisches/flings, polkas, mazurkas, marches, waltzes and barn dances. This abrupt change in repertoire has occurred among musicians all over Ireland, including the Gaeltacht of the west, leaving a gap in the modern Irish repertoire relative to that of the other countries in this study, where the repertoire of 'traditional' dance music played today in Australia, England and South Africa is not particularly different in its mix of dance types than that once played by Carolan, O'Dwyer and Hourican.

But is it traditional music? A concertina and a banjo playing for round dances, England 1890s.

The story of what happened to early ballroom dance music in Ireland, after a half century of suppression and banishment by clerical, patriotic and government groups, is an important one, not just historically and sociologically, but because of the strong impact it had on concertina playing, both on the repertoire played and on the playing styles employed. It is safe to say that when house dances were banned in Ireland, the concertina nearly died out too - along with most locally composed Irish ballroom dance tunes. If we rejoice in the great nineteenth century collections of Irish music (O'Neill's work has been called A Harvest Saved ![]() 47) then we must also consider the harvest of locally composed square and round dance music that was lost, never to be recorded by collectors and their recording machines.

47) then we must also consider the harvest of locally composed square and round dance music that was lost, never to be recorded by collectors and their recording machines.

The German concertina came to Ireland during this time of great cultural change, and because it was inexpensive and easy to learn it helped fill the gap left by departing professional musicians. This instrument, along with the button accordion and the mouth harp, accompanied an invasion of ballroom dances from central Europe: a popular craze, that had global dimensions. The 1867 dance book of Dundalk resident Kate Hughes contains instructions for eight sets of quadrilles and eight set dances 'of quadrille type', including Caledonians, Lancers, mazurka quadrilles, and waltz cotillons. There were also instructions for some 54 English-style country dances. The dance book only contains instructions for only two reels.![]() 50 As Breandan Breathnach noted, 'Before the end of the last [nineteenth] century the sets and half sets had pervaded the country and had completely ousted the old solo dances, jigs, reels and hornpipes, and the group dances based on them...'

50 As Breandan Breathnach noted, 'Before the end of the last [nineteenth] century the sets and half sets had pervaded the country and had completely ousted the old solo dances, jigs, reels and hornpipes, and the group dances based on them...'![]() 51

51

An Irish dancing class in New York, 1905. The dancers are learning the 'Irish quadrille',

at a time when the quadrille was being banned as 'foreign' back in Ireland.

From the American Memory collection, Library of Congress.

And then there were the round dances. As Helen Brennan notes:

A group of farmers and townspeople from Athea , Co Limerick, celebrating the potato harvest, 1911.

Several on the right are preparing boxty for the party, and a concertinist (May Nan Stevens)

is ready to play for the dance that would accompany the celebration.

With thanks to the National Folklore Collection, University College Dublin, and to Sean O'Dwyer and Nora Hurley.

A decade later in 1906 music collector Francis O'Neill returned for the first time to the Ireland of his youth, noting that:

Country people, including those in the Gaeltacht, saw this somewhat differently, and voted with their feet. Witness the recollections of Patrick Flynn, of rural Loughrea in County Galway:

Dances were mostly held in farm kitchens ... Waltz, Polka, and Lancers were the thing. Reel sets were for the lesser breeds, without the law.![]() 56

56

Wooden road-side [dancing] platforms were set on fire by curates; surer still, the priests drove their cars backwards and forwards over the timber platforms; concertinas were sent flying into hill streams and those who played music at dances were branded as outcasts.![]() 59

59

Fathers of this parish, if your girls do not obey you, if they are not in at the hour appointed, lay the lash upon their backs. That was the good old system and that should be the system to-day.![]() 61

61

Music collector Frank Roche, who alone among Irish music collectors of that era made room for some of the old ballroom dances in his collections of Irish music, observed in 1927:

So, they barred the country house dance, and the priests was erecting parish halls. All they wanted was to make money - and they got 3d. into every shilling tax out of the tickets to pay the government for tax. So the country house dance was knocked out then, and 'twas fox-trots, and big old bands coming down, and our type, we'd be in a foreign country then. We couldn't put up with it at all, the noise and the microphones, and jazz and so on ... the music nearly died out altogether - Irish music. Then the emigration started, a lot of the lads I used to play with went off to England and America, and there was no-one but myself - Scully was dead - and I used to go down the road, and I used, honest to God, I used to nearly cry. Nowhere to go, no-one to meet, no sets in the houses, nothing left but the hall ...![]() 65

65

Music collectors turned their back on these dance tunes. Francis O'Neill despised them and transcribed none. Even Breathnach, in his definitive and relatively recent collection of Irish music, could only bring himself to include polkas, largely because they had been incorporated (albeit in a rhythmically modified form) along with Irish double reels into the sets, which were revived by various organizations during the 1970s and 1980s. Other than a few handfuls of schottisches, barn dances, and mazurkas transcribed by Roche in 1927, and a few recordings of aging musicians made by Ciarán Mac Mathúna of RTÉ and others, the Irish ballroom dance repertoire - much of it comprised of modifications on imported tunes as well as completely locally-composed tunes - was largely lost. In the Australian, South African, North American and British traditional music repertoire, there are thousands of such tunes nestled away in collections, and they are regarded as part of each country's cultural heritage. Not so in Ireland, where round dances even today are often considered as foreign.

Attitudes are slowly changing, however. There has been a great resurgence of set dancing in Ireland, albeit to 'Irish-ized' music, and many of these dance evenings now include a schottische, a Shoe the Donkey varsoviana, or a Stack of Barley barndance.![]() 67 Set dancers, it seems, are keenly aware of history and sympathetic to these lost dance forms. Schottisches/flings, polkas, barn dance and quadrille tunes are now allowed in Irish music competitions of the Comhaltas Ceoltóiri Éireann, and that organization has preserved old field recordings of schottisches, polkas and waltzes in its audio archive. Topic records produced a recording of 'Irish country-house music' in 2001 that gathered early twentieth century recordings of Irish musicians, especially emigrés in America, who continued to play ballroom dance music after the ban in Ireland.

67 Set dancers, it seems, are keenly aware of history and sympathetic to these lost dance forms. Schottisches/flings, polkas, barn dance and quadrille tunes are now allowed in Irish music competitions of the Comhaltas Ceoltóiri Éireann, and that organization has preserved old field recordings of schottisches, polkas and waltzes in its audio archive. Topic records produced a recording of 'Irish country-house music' in 2001 that gathered early twentieth century recordings of Irish musicians, especially emigrés in America, who continued to play ballroom dance music after the ban in Ireland.![]() 68

68

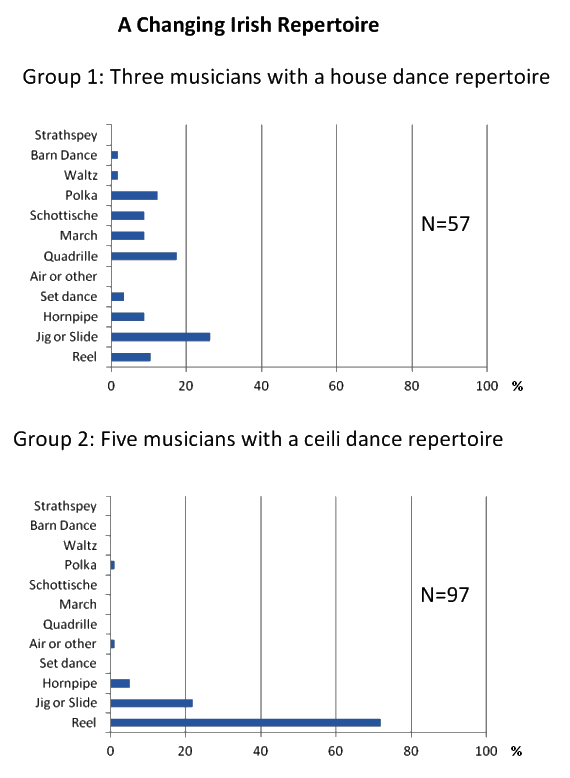

But for the most part, the currently played traditional repertoire in Ireland that stems from the house dance period is very lean, indeed. From the beginning of the céilí dances, Irish concertina players have concentrated on learning reels and jigs to the exclusion of almost everything else. An adjacent chart compares the same group of three women whose repertoire, recorded in their senior years, firmly reflects the house dance era (Carolan, O'Dwyer and Hourican) versus a four men (and one woman) of the same general range of birth years who chose in their later years to play a repertoire that reflected the céilí dance era that replaced it. Their music and this chart are explored in Chapter 8, below. Women players in Ireland tended to play in the home rather than in pubs, and were thus less exposed to changing fashions of music. The one woman in the second group, Elizabeth Crotty, played often in her family's pub, and also was an officer in Comhaltas Ceoltóiri Éireann, where the renewed céilí dance repertoire was preferred.

A comparison of dance types in the repertoire of two groups of contemporaneous Irish concertina players.

Tune counts (shown in percentages of total) include those of all known recordings for each individual,

and include a total of 57 separate tunes from group 1, and 97 from group 2.

The second group has narrowed its focus greatly on reels and jigs.

Group 1: Mary Ann Carolan, Ella Mae O'Dwyer; Katey Hourican, who played a house dance repertoire.

Group 2: William Mullaly; Patrick Flanagan; Tom Barry; Elizabeth Crotty; Michael Doyle,

whose playing reflected the céilí dance repertoire.

Beyond repertoire, the ways in which the concertina was played also changed dramatically as a result of the banning of the house dance. After the Public Dance Hall Act, dances moved from small neighborhood houses to large parish and community halls. Whereas a solo concertina or fiddle player had long been thought adequate for a house dance, groups of musicians were needed to fill the larger volume of space in public dance halls. These new céilí bands had a varied instrumentation of fiddles, flutes, pianos, drums, and accordions playing together, and most of these musicians preferred the 'fiddle' keys of G, D, and A to the old key of C (and G) used by the those who played German concertinas. Playing in the keys of D and A requires a third row of buttons on a concertina, and most German concertinas only had two rows. Many if not most concertina players gave up playing at this time, due to the double whammy of changing repertoire and changing keys.

The Green Isle Céili Band, 1950s. Donnie Connor, first president of the Tulla Comhaltas,

is seated at right, holding a German concertina. Céili dances with large bands

replaced the earlier house dances that typically had solo musicians.

Relatively few céili band musicians played the German concertina. Photo courtesy of Tulla Comhaltas.

By the 1950s, the few remaining Irish concertina players, by then mostly men concentrated in County Clare, had moved from the old octave style of playing to a single-note, along-the-row style, the better to keep up with reel tempo for the new Irish dance repertoire, and the better to play in the keys of G, D and A. Reels in Ireland had always been played mostly singly (one note at a time) and along-the-row, largely because of their rapid tempo. With the advent of the céilí dances, these more rapid reels and jigs dominated the repertoire, and a new generation of concertina players began to adjust its playing style accordingly, playing almost everything in that manner. By far, most of the concertina players who were recorded during the 1970s played in this new manner, for example Tommy McCarthy, Bernard O'Sullivan, John Kelly, Solus Lillus, and Packie Russell. Solus Lillis, a blacksmith from Clonreddan, near Cooraclare in West Clare, recalled the older generation - the house dance generation - as follows:

During the revival of Irish music of the latter half of the twentieth century, playing styles changed again when concertinas began to be played for judges at competitions as well as for listeners in pub sessions. Inevitably, concertina players began to play in a more ornamented style and at a more rapid tempo, the better to hold the attention of a static listener. The result today is a highly ornate style, played singly, within a reel-rich repertoire that bears little resemblance to that of the Irish musicians of the house dance era. This is not to criticize the modern style, as it has won thousands of converts to Irish traditional music and to the concertina, and there is much to commend in its beauty and gracefulness. It seems a pity, however, that so few in Ireland play tunes of the house dance repertoire and in the old style today.

In the other three countries, all of which were spared the early twentieth century cultural warfare that plagued Irish music and dance, the ballroom dance repertoire has remained largely intact amongst modern day 'traditional' musicians, although of course the general, worldwide collapse of most forms of European social dance in the present era is well known. In England, it could be said that ballroom dance music was ignored by folk music authorities until an 'English Country Music' movement began in the 1970s, turning a spotlight on surviving rural musicians there who still played many ballroom dance tunes alongside tunes of the older step-dance and country dance genres, in country pubs. In South Africa, another small movement has begun within the Tradisionele Boeremusiekklub to preserve the old style of playing the two-row German boerekonsertina, in octaves with associated chords. New German-style instruments are now being produced there in order to help that movement to grow. In Australia, collecting efforts of both traditional music and dance began in the 1950s, and as a result old time music and dance were passed on to a newer (albeit less numerous) generation before the last of the old guard had passed away. As we shall see in Chapter 11, there are still a few players in rural Australia and South Africa who both play for ballroom dance and still play in the old octave playing style.

46. As of writing, there are two published CDs featuring Edel Fox, two of Claire Keville, and on for Dympna O'Sullivan.

47. Nicholas Carolan, 1997, A Harvest Saved: Francis O'Neill and Irish Music in Chicago. Ossian Publications, Cork, 79pp.

48. E G Ravenstein, 'On the Celtic Languages of the British Isles: A Statistical Survey', Journal of the Statistical Society of London, vol.42, no.3 (1879), p.584. Citation found in Wikipedia, History of the Irish Language. Note: A good map-based summary of the famine and its cultural aftermath in Ireland may be found at http://www.irelandstory.com

49. Francis O'Neill, Irish Folk Music, a Fascinating Hobby (1910; repr. Darby, Pennsylvania: Norwood Editions, 1972), p.288.

50. Frank Maginnis, Joan Flett and Chirs Brady, Kate Hughes' Dancing Book, Dundalk, 1867 (online at www.chrisbrady.itgo.com/dance/dundalk, 2002).

51. Breandán Breathnach, Dancing in Ireland: Dal gCais, 1983, p.27.

52. Helen Brennan, 1999, p.28.

53. Donal McCartney, 'From Parnell to Pearse', The Course of Irish History (Cork: Mercier Press, 1967), pp.295-296.

54. Anonymous, 'The revival of Irish Literature, and other addresses, 1894', The Quarterly Review, 190 (London: John Murray, 1899), p.17.

55. Francis O'Neill, Irish Folk Music, a Fascinating Hobby, (1910, repr.Norwood Editions 1972), p.288.

56. Helen Brennan, 1999, p.109.

57. Helen Brennan, op.cit., p.105.

58. W P Ryan, 1912, The Pope's Green Island: London, J Nisbet. Quoted in Helen Brennan, op.cit.

59. Bryan MacMahon, 1954, The Vanishing Ireland: Dublin, O'Brien Press, p.212.

60. Irish Catholic Directory, 1925, p.563. Quoted in Breandán Breathnach, The Church and Dancing in Ireland: Dal gCais, 1982, pp.59-71.

61. Ibid, p.568.

62. Breandán Breathnach, The Church and Dancing in Ireland: Dal gCais, 1982, pp.59-71.

63. Anonymous 'Gaedeal,' writing in The Western People, Mayo, 27 August and 4 September 1904. As quoted in Helen Brennan, op.cit., p.32.

64. Junior Crehan, as quoted in Larry Lynch, 1991, p.43.

65. Recorded conversation between Junior Crehan and Barry Taylor, Ballymackea, County Clare, 8 July 1976.

66. Breandán Breathnach, 1983, Dancing in Ireland: Dal gCais, 1983, p.27.

67. See for example Bill Lynch's online Set Dancing News, www.setdancingnews.net

68. Reg Hall, ed., Round the House and Mind the Dresser: Irish Country-House Dance Music: Topic Records, London, CD TSCD606, with liner notes by Reg Hall.

69. Ibid., p.175.

| NEXT |