Colonial Australia was a very sparsely populated country in the late nineteenth century, when dances provided a very special type of social 'glue' to small rural communities. A good example is provided by a report of a dance in the small village of Newcastle (now called Toodyay), in the Avon Valley of Western Australia, perhaps fifty miles northeast of Perth, in 1875:

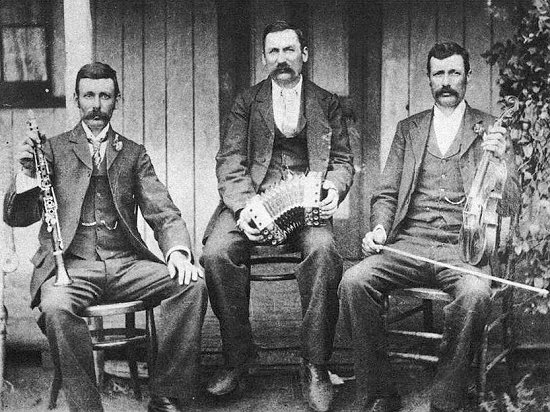

The Colemane brothers circa 1890, including Alfred Colemane (ca.1837-1912) on German concertina.

They played for dances in Cootamundra, New South Wales.

From the Bush Music Club's 'Singabout Magazine', 1966, with thanks to Bob Bolton.

A 1908 non-fictional account by an Anglican parson paints a detailed picture of a 'bush dance':

The dancers, they'd start at eight o'clock. They'd go all night, of course. I'd be playing, and I'd get a bit of a lunch at half past one, and I'd play on until four o'clock. Because the ladies, or the girls, weren't allowed to leave until daylight, the breaking day ... so they wouldn't get away with somebody.![]() 3

3

A perhaps more pertinent reason for such all night dances involved the dangers of nighttime travel in the bush, including encountering flooded rivers and open mining shafts, among other things.

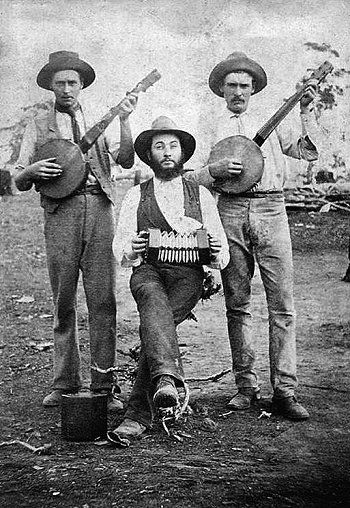

Anglo-German concertina player with two fretless banjo players, Australia, ca.1870.

With thanks to Peter Cuffley and Peter Ellis.

The era of informal house and woolshed dances (now termed 'bush' dances, although that is a modern term that would have been relatively unfamiliar back then when they were typically called 'balls') lasted well into the early twentieth century in many rural areas, and because of the numerous field recordings of surviving players from that era we have a very good idea of how the tunes were played. Stylistically, these Australian concertinists were nearly all octave players who played sparsely, with few if any ornaments - not unlike early players in Ireland and England. This is not surprising, as they all shared a common purpose: playing for house (and barn and woolshed) dances. Dancers needed volume and a rhythmic beat, and the musicians needed to have stamina for playing, often solo, for all night dances. Some players used a frequent pulsation of partial chords in the manner of a William Kimber, and many others had the sparse, rhythmic but much less chorded style of Scan Tester or Katey Hourican.

It is likely that these styles for playing the concertina were developed independently and locally, and did not arrive with immigrant players from Ireland or England, because the ballroom dances, their accompanying repertoire of music, and the concertina arrived in all of these countries simultaneously. Players in isolated rural areas devised their own ways of dealing with the demands of house dances, and seem to have all gravitated naturally to the use of octaves to produce volume. Earlier immigrants did bring step dances (jigs, reels and hornpipes) and country dances with them, in the early Colonial period, but they arrived playing these tunes on fiddles and flutes. By the time that the concertina arrived in the 1850s, and as it became established in the 1860s, quadrilles and round dances were all the popular rage not only in the colony but in the 'mother countries' of England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland, and it is this nineteenth century ballroom dance repertoire that is most remembered by the concertina players who survived into the middle of the twentieth century.

Bush dances were essentially gone from most areas by the 1930s, and field collection of bush music began in the 1950s. Of particular importance to the concertina enthusiast is the work of John Meredith, who in the process of compiling his two-volume treatise on the Folk Songs of Australia, published in 1967 and 1987, encountered and recorded the music of a number of rural concertina players, as well as the music of descendants of former concertina players, many of whom had moved on to the accordion. Meredith, along with later folk music collectors like Rob Willis, Warren Fahey and Peter Ellis, recorded perhaps a dozen or more surviving concertina players from the heyday of the instrument.

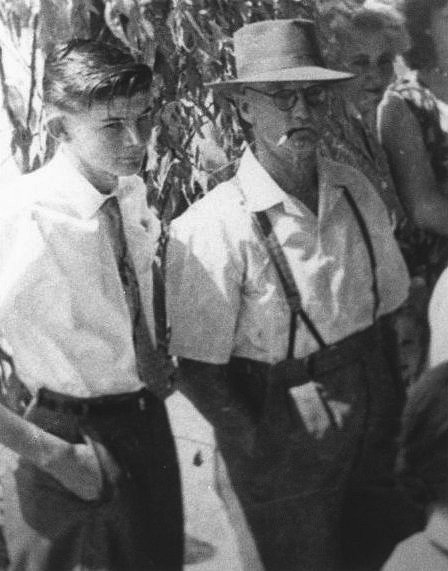

John Meredith (with accordion) and Peter Ellis (with concertina) on a folk music

collecting trip in Western Australia, 1991. Photo courtesy of Peter Ellis.

The collection of the colonial era dances - both the global ballroom dances and their local variants - arguably began with the efforts of Shirley Andrews, of Melbourne. She began her research into early Australian dance in the 1950s and quickly learned that the common assumption that dancing in Australia was based upon earlier dances brought from the British Isles was incorrect, and that Australia, like England, Ireland and South Africa, had followed the latest fashions in overseas ballroom dances throughout the late nineteenth century. In 1962, her work was greatly aided by the discovery of the Klippel family and others in the Nariel Valley of Victoria who were still dancing many of the ballroom dances of the late colonial era in their community dance hall (Con Klippel is one of the recorded players below).![]() 4

4

The old community dance hall in Nariel, northeastern Victoria

By the 1970s, traditional-style bush dances were being resurrected at festivals all over Australia, with the help of a number of bush music and dance societies, among them the Sydney Bush Music Club, the Bush Dance and Music Club of Bendigo Victoria, the Victorian Folk Music Club of Melbourne, and the Wongawilli Colonial Dance Club in Illawarra, New South Wales. A key annual event is the National Folk Festival held in Canberra A.C.T., which started as a venue for bush dances.

A significant number of concertina players are active with these societies and festivals, and a number of these musicians continue to play in the traditional octave style - many more than in England and Ireland, even though overall numbers of concertina players are much lower than in those other countries. At the same time, however, trends are moving away from such players. One such trend is the tendency of festivals like the National to expand in the direction of a wide variety of concert performers for listening audiences (a traditional concertina performer recently described them as "bums on seats") rather than the participatory dances of the recent past, where the musicians and the dancers shared a symbiotic bond. As will be demonstrated in Chapter 8 below, playing for listening ultimately changes the music that is played. Additionally, younger concertina players in Australia are increasingly coming under the spell of imported modern, highly ornamented styles of playing from Ireland that are also mainly aimed at listeners rather than dancers, and which favor a repertoire that is largely alien to the round and square ballroom dances that both countries once shared. At the end of the day, the survival of older styles of Anglo playing in Australia seems to depend upon the survival of old time dances.

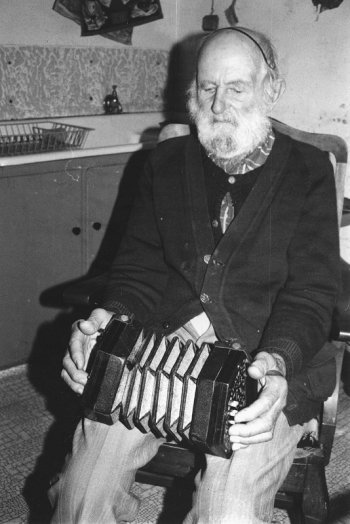

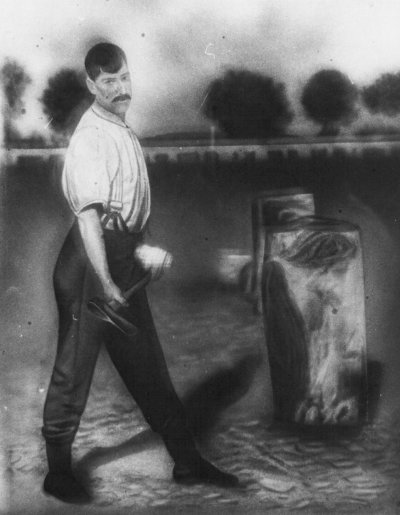

Although of English descent, Chapman's parents were both born in New South Wales; his mother was from Coborrah. His was a musical family; his father and an uncle played violin, and his brothers and sisters played violin, concertina, and piano. Chapman began playing concertina at the age of ten, and began playing for local house parties and dances. In his younger years, Chapman was a farmer, but he later built concrete silos and sheep dips for a living. As bush dances were dying out in the 1920s, Chapman extended his playing days by teaming up with his sister Grace on piano. He played for dances as late as World War II; such dances returned briefly as feelings of Australian patriotism rose during the war.

Dooley Chapman in his kitchen. Photo courtesy of Chris Sullivan.

Chapman's repertoire reflects the key dances of his era: round dances such as waltzes, polkas, mazurkas, schottisches, breakdowns, and varsovianas; as well as quadrilles such as the Lancers and the Alberts. He also played the odd jig for step dancers, although the ballroom dance styles were more central to his experience.![]() 6 Although he lived in an out-of-the-way rural area in a time before radio and television, Chapman's repertoire reflects a global tune resource, just as does the repertoire of all recorded early Australian players. Old Dan Tucker came from the minstrel shows, his Varsoviana from continental Europe. The Alberts Quadrille and the Highland Schottische had English and Scottish origins. He played a breakdown to the tune of Ring the Bell Watchman, an American song of Civil War vintage that was also in Susan Colley's repertoire. Other tunes appear to be of local origin.

6 Although he lived in an out-of-the-way rural area in a time before radio and television, Chapman's repertoire reflects a global tune resource, just as does the repertoire of all recorded early Australian players. Old Dan Tucker came from the minstrel shows, his Varsoviana from continental Europe. The Alberts Quadrille and the Highland Schottische had English and Scottish origins. He played a breakdown to the tune of Ring the Bell Watchman, an American song of Civil War vintage that was also in Susan Colley's repertoire. Other tunes appear to be of local origin.

Chapman's musical mentor was his cousin Billy Chandler (ca.1870-1905), who played a Bb/F concertina made by John Stanley of Bathurst. Billy Chandler played for dances all over the region, using a bicycle for transport, as Chapman recalled:

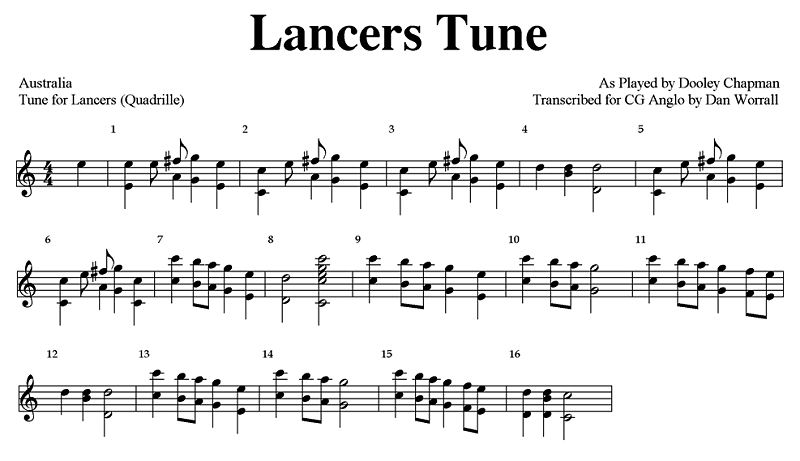

A quadrille tune, the Lancers Tune, is played in an octave style in the key of C, and the melody weaves back and forth between the C row and the G row. In general, lower passages are played on the C row, and higher passages on the G row. An oddity of Chapman's playing, as well as several other Australian players, is the use of an F# in a key that is in C, and thus should have no sharps. This gives the tune an odd modal sound. It happens because the cross-row transition from the C row to the G row in the playing of the C scale should happen between the solfège fa, F (on the C row) and the sol, G (on the G row. See discussion, Chapter 12). In Chapman's case, he sometimes places that cross-row transition between mi, E (on the C row) and fa, F# (on the G row, where the F is sharped). The practice seems intentional, as a full look at his music suggests.

Dooley Chapman's Lancers Tune, Quadrille. Transcribed for C/G Anglo by Dan Worrall.

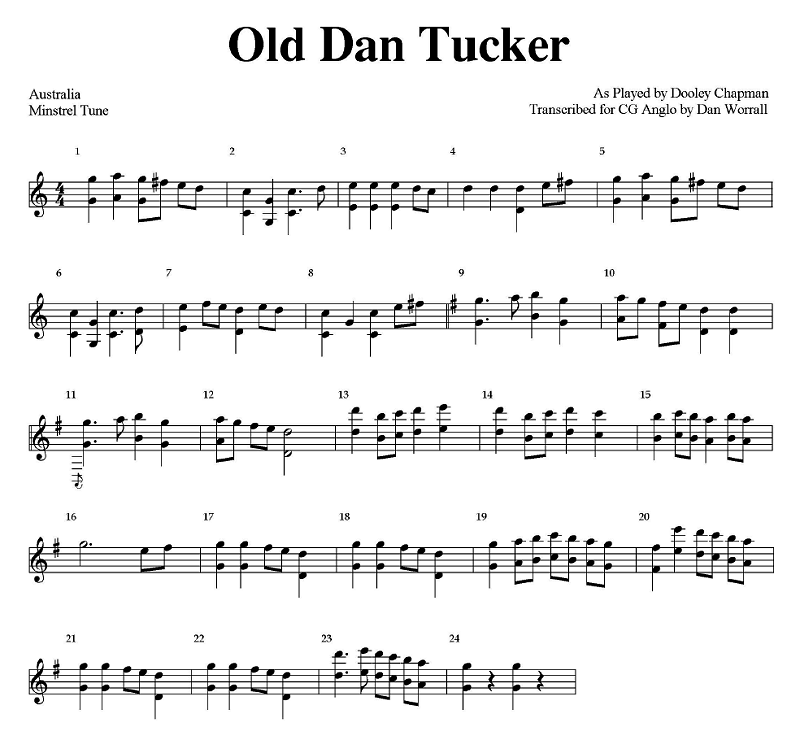

The American minstrel tune Old Dan Tucker was popularized by Dan Emmett and the Virginia Minstrels in 1843, who spread the tune worldwide. Played as a breakdown in its original form (a tune in common time where the emphasis falls on the second and fourth beat), it has clearly made a number of melodic and rhythmic changes before coming to Chapman. It is played in the key of C in a similar two-row octave manner, starting on the G row. In it, Chapman again uses an F# in the A part that is not in keeping with the rest of that passage, which is clearly in the key of C.

Dooley Chapman's Old Dan Tucker: minstrel tune. Transcribed for C/G Anglo by Dan Worrall.

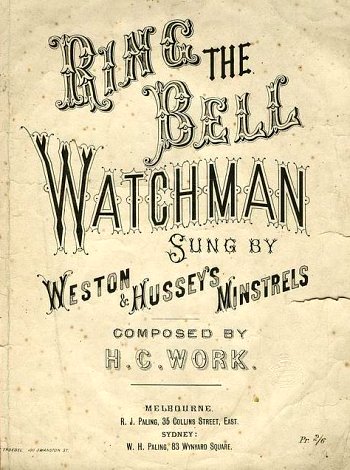

Dooley Chapman's Ring the Bell, Watchman was written by Henry C Work in 1865 as a victory song at the end of the American Civil War. It was spread by minstrel groups, and became a very popular song in Australia; it was universally known and played by old time concertina players there, and remains popular today (a version of it played by New South Wales musician George Bennett is included below). An attached cover to an 1868 Australian version of the song shows how quickly tunes like this moved across the oceans into the popular music repertoire. Its melody was later attached to an Australian verse, becoming Click Goes the Shears, an iconic Australian folk song. That verse was later popularized by American Burl Ives in the 1950s, a recording that became popular across Australia.

A version of Ring the Bell Watchman published in Melbourne, 1868.

From the National Library of Australia.

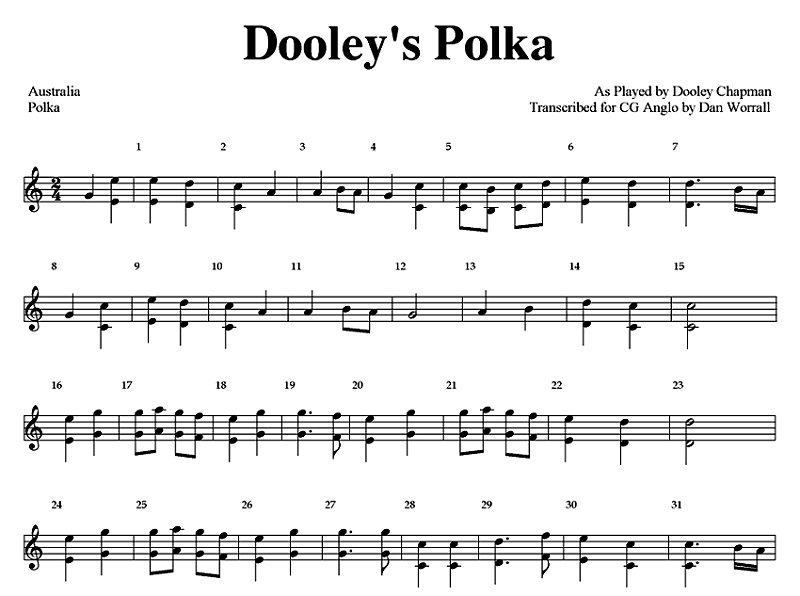

An Untitled Polka by Chapman (termed Dooley's Polka in the following transcription) has affinities in its A part with the Irish song Bog Down in the Valley, and with the old song Oft in the Stilly Night, composed by Thomas Moore, but varies significantly in the B part relative to both of these. It was played with piano accompaniment. Chapman said in an interview that playing with a piano accompaniment provided by his daughter extended his playing years for dancing significantly; the piano added more respectability to the music at a time when the solo concertina began to be seen as a bit old-fashioned and rural. It is a simple tune, played mostly in octaves, and the entire tune is played on the C row.

Dooley Chapman's Polka. Transcribed for C/G Anglo by Dan Worrall.

The Starry Night Waltz is a local version of Starry Night for a Ramble, which seems to have been a song from the London music halls, with the earliest known broadsheet of it published there in about 1854. It was popular in Australia from the goldfield days, and like the previous song it is widely known to the present day. Chapman's A part of the tune is modified slightly from the commonly known version. John Meredith collected this tune from a number of sources during his research in the 1950s and 1980s. This recording of Chapman was made by Bob Campbell in 1974, and was kindly made available by Alan Musgrove.

George Bennett was a timber worker who cut pine logs for the local mill. As the following photograph shows, he was a champion axeman, and he won the woodchop event at the Gunnedah show six years in a row. Jim and George also sheared sheep in this wool-producing region. At one stage, George worked at the Gunnedah coal mine, which had opened in the late 1870s. In a tragic accident, he lost a leg while working the coal cutting machine. Undeterred, and turning his woodworking skills to use, he began designing and making wooden legs.

George Bennett (1878-1966) in his years as a champion axeman,

in the late 1890s. Photo courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

Both George and his brother Jim Bennett (1881-1978) played both button accordion and concertina for local dances, and both were singers. In the early to middle 1960s, when George was in his mid-eighties, his family recorded him on a small reel to reel tape recorder. Willis and Meredith learned of these recordings of George and Jim when they first visited George's son Ken in 1992, by which time the two brothers were deceased. Attempts to make a copy of the tapes at that time failed, as Ken's house had no electricity. Rob Willis returned in 2001 with John Harpley, and the two managed to copy and preserve the recordings. They are now housed at the National Library of Australia, which has made them available for this archive.

By the time of the Meredith and Willis visit in 1992, the bellows on George's Stanley concertina had deteriorated, and had been replaced by the bellows of an old German concertina (sometimes known in Australia, somewhat derisively, as a "chinese lantern concertina."). The adjacent photograph shows Ken playing that instrument at the time of the 1992 visit.

Ken Bennett, Gunnedah Australia, 1992.

He is holding his father, George Bennett's,

Stanley concertina, with its modified bellows.

George Bennett's playing on this tape made in the 1960s is lively and vigorous despite his advanced age. He appears to be pacing through his repertoire, tune by tune, in order to please his family members, who wished to preserve his music. There are a number of songs as well as song tunes, as well as a large variety of dance tunes from the late nineteenth and very early twentieth century: waltzes, schottisches, polkas, a galop, jigs, breakdowns, quadrilles, and varsovianas...a trove of about sixty separate tunes and songs. Because of their quality and abundance, as well as importance, some eighteen dance and song tunes, and one song, are included in this archive.

Dick Cribb is a single reel, or perhaps more correctly, a breakdown, so classified because of the great emphasis on the second and fourth beat (off-beat) in Bennett's version of the tune. Its origin is unknown, but seems to show minstrel influence in its off-beat breakdown rhythm, which is not particularly common among Australian players. Bennett plays the tune in Bb on his Bb/F Stanley concertina. A search on present day persons named Dick Cribbs in Australia turned up one, in nearby Queensland, who is active in an environmental group called 'Men of the Trees;' perhaps an ancestor was a timber colleague of Bennett's? At very least, the unusual surname Cribb is found in Bennett's general region.

Bennett plays Dick Cribb all in octaves in the classic traditional style, mostly on the Bb row but with a cross-row transition to the F row in the higher pitched beginning of the B part. The off-beat breakdown rhythm is produced in an unusual manner, by adding partial chords to the right hand side on the offbeat; most players restrict such chords to the left hand. This higher pitched offbeat rhythm is somewhat reminiscent to the sound of a clawhammer banjo, hence the suggestion of minstrel influence.

Waltzes. [I'll Be] All Smiles Tonight is one of a large number of waltzes in Bennett's repertoire. It is an American sentimental song, written by T B Ransom in 1879 but was resurrected by generations of bluegrass and country and western singers, including the Blue Ridge Highballers in 1926, the Carter family, Mac Wiseman, Johnny Cash, and even the Chieftains. Bennett plays it in the key of F, entirely on the F row, and mostly in octaves with some left hand partial chords.

Break the News to Mother is an American sentimental song written by Charles K Harris, the "King of the Tear-Jerker," who wrote the global hit waltz and song After the Ball [Is Over] in 1892. Break the News to Mother was originally written in 1891 about a dying firefighter, but was not successful. It was re-written in 1897 about a dying soldier of the Spanish-American soldier, and became an instant hit. Bennett plays this tune on a German concertina that is pitched in GD. He plays it in the key of D, mostly on the G row.

The Gundawindi Waltz (probably named for Goondawindi, Queensland) appears to be of Australian origin. He plays it on his G/D German concertina, in the key of D, in a similar manner to the above waltz.

Darling Wait 'Til Morn, another sentimental waltz tune, is played in the key of F.

Two Little Girls in Blue was composed in 1893 by Charles Graham, an American composer, and was popularized by the minstrel shows. It later was used in a Broadway play of that name written by Paul Lannin and Vincent Youmans, with lyrics by Ira Gershwin, that premiered in 1921. Its title song became a global hit as both a song and a waltz tune. Bennett plays it in the keys and manner of the above three waltzes.

Other dance tunes. George Bennett played several step dance tunes, all jigs. What'll They Do if the Billy Boils Over is a version of the Irish jig St Patrick's Day, and is played in Bb.

The Rakes of Mallow is of probable Irish origin, and is one of those global tunes that is seemingly known by everyone who plays traditional dance music. It is a single reel, usually played for a quadrille. Bennett plays it in Bb in octaves, with chords at ends of phrases. The A part is played wholly on the Bb row, and the B part is played in a cross-row manner.

Bennett played a number of polkas, among them the following two. Turn That Old Man Around is a polka of unknown, perhaps local origin, played in a cross-row manner in the key of F.

Bennett plays the old schottische Old Time Schottische is played in F, modulating to Bb in the B part.

He played a jig for a figure of The Lancers quadrille; it is in the key of Bb, modulating to F in the B part.

The Varsoviana was a popular dance in late Colonial Australia, and a great number of tunes have survived for it. Many are variants of the globally known standard tune, as is this one. He plays it in F, mostly on the F row.

Almost everyone, it seems, knew Ring the Bell, Watchman; Dooley Chapman's version is included above. George Bennett played his in F, in octaves, and in a cross-row manner between the two rows. Chapman played it all on the middle row (the C row on his C/G Anglo).

Although not a concertina tune, Bennett's song The Capture of the Kelly Gang relates an event that had connections with the concertina, and is a superb Australian folk ballad. In Australia, Ned Kelly (1854-1880) remains a controversial person, and one's opinion of him depends largely on whether one supports law and order and frontier justice, or sympathizes with working class persons (especially Irish immigrants) who found the British constabulary to be overbearing and arrogant in their work. Kelly was born in Victoria to Irish parents, and fell into trouble with the law early, becoming an outlaw after he and his gang killed three policemen at Stringybark Creek in 1878. As a result they were outlawed by act of the Victorian parliament, which was basically a 'wanted, dead or alive' decree. Later that same year, he and his gang raided the National Bank at Euroa on December 10, and the Jerilderie bank on February 8, 1879.

Still on the run months later, the Kelly gang arrived in the small town of Glenrowan, Victoria on June 27th, which set into motion a classic set of events that ended the careers of all in the gang. They took about seventy hostages at the Glenrowan Inn, then ordered the town's railroad tracks pulled up, as they knew the police were on the way via the train and they wished to derail it. In the hotel were the Kelly gang members - Ned, brother Dan, Joe Byrne, and Steve Hart - along with a captured constable named O'Sullivan and all the hostages. All were tensely waiting for events to unfold, according to the following account by Constable O'Sullivan:

A period illustration of the quadrilles danced by the Kelly gang

as they awaited the police at the Glenrowan hotel.

Note the solo concertina player at left.

Picture courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

The town's schoolmaster, a hostage who had earlier been released by the gang, alerted the police train to the danger imposed by the destroyed rails. All was now in place for the climactic shootout. Each of the four men was equipped with homemade body armor made of steel plate, but only Ned was outside when the shooting began. Dismounting his horse when a bolt in his armor failed, he was shot in the arm and legs, which were unprotected. The other three members died in the hotel, which was set ablaze by the police. Byrne bled to death as he poured himself a final glass of whiskey at the bar, and Dan Kelly and Steve Hart reportedly committed suicide. Ned Kelly stood trial and was hanged in 1880, later to become an Australian folk hero. His skeletal remains were recently identified from DNA evidence, after they had long been lost; plans to reinter the remains at Glenrowan are in the works.

Bennett believed that Kelly was a hero, as the first stanza of his ballad suggests:

Con Klippel with two-row Anglo-German concertina, ca.1970.

With thanks to Peter Ellis and Keith Klippel.

Con Klippel, the grandson of the German immigrant, worked in many jobs, some related to farming, the others involving insurance sales and managing a fleet of school buses. He mostly played accordion, but also played concertina and a variety of other instruments, and along with Shirley Andrews and other musicians and dancers of the Nariel area, was instrumental in reviving old time music and dance in the Nariel Valley in the 1960s and 1970s. He died on stage in 1975 while playing his concertina for a dance.

Klippel's Old-Time Dance Band, Nariel Victoria, 1973. Left to right;

Sid Simpson, Charlie Fardon (MC), Betty Coulston, Keith Klippel, Neville Simpson,

Con Klippel, George Klippel. With thanks to Peter Ellis.

In the following recording made in 1969 he describes the dances that were performed on one of the early meetings with Shirley Andrews and other members of the Folklore Society of Victoria (based in urban Melbourne) in the early 1960s, when they visited Nariel and became awestruck that so many of the old dances had survived out in the bush (despite the fact that such dances were still being held at other country districts in Victoria, in addition to Nariel.![]() 9) The list of still-active dance types performed on one of those occasions, as listed by Klippel in this recording, is very long and rich. This and other recordings of him are included here courtesy of his son, Keith Klippel. Keith Klippel, a third-generation concertina player and fourth-generation free-reed player, continues the tradition by playing accordion and concertina for local dances in Nariel. A tune from Keith is included in Chapter 11.

9) The list of still-active dance types performed on one of those occasions, as listed by Klippel in this recording, is very long and rich. This and other recordings of him are included here courtesy of his son, Keith Klippel. Keith Klippel, a third-generation concertina player and fourth-generation free-reed player, continues the tradition by playing accordion and concertina for local dances in Nariel. A tune from Keith is included in Chapter 11.

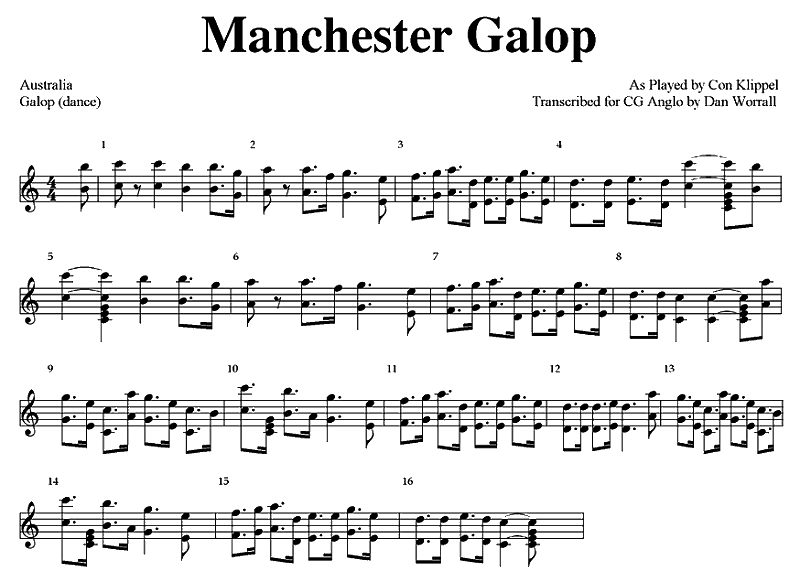

The Manchester Galop was brought to Australia from Germany by Klippel's immigrant grandfather, according to family history. The galop is a vigorous dance, and for that reason was often the last dance of the evening. This dance however is usually done less vigorously in Australia, more like a two-step or a schottische. It is played by Con Klippel in the key of C, entirely on the C row, in octaves on his two row Lachenal Anglo CG concertina. Con Klippel was fond of swinging his concertina around in a windmill pattern while playing this tune.

Conrad Klippel's Manchester Galop. Transcribed for C/G Anglo by Dan Worrall.

Grandmother Klippel's Schottische is another of the tunes associated with the Klippel family. It is also played in the key of C, in octaves, and entirely on the C row, with additions of phrase-ending C chords.

Arthur Byatt's Schottische is named for a Thougla (Nariel area) musician. It is played in the key of C, and like the previous tune is played entirely on the C row.

The Mill Belongs to Sandy is a single reel typically used in quadrilles. It is derived from a children's rhyme that is also known in England, Ireland, and America. Like Con's other tunes, it is played in octaves all on the C row.

Me Smokey Smokey is a song tune that was composed by Con Klippel, and again is played in C, in octaves, and on the C row. From this limited collection of concertina recordings, one can gather that Con was always a one-row player on his Anglo. This probably developed from his main instrument, the one row button accordion. Both instruments define the popular melodies and dance tunes of the Nariel Valley.

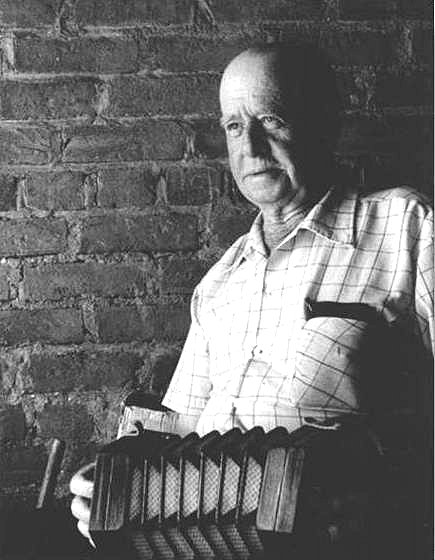

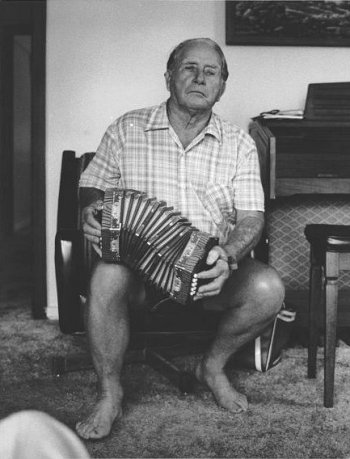

Jim Harrison of Khancoban, New South Wales, with his concertina, 1986.

Photograph by John Meredith; from the archives of the National Library of Australia.

Harrison played for dances in the Khancoban School with his friend Rob Scammell; both played accordion and concertina. Sometimes they ventured into Nariel valley, as well as the district around Corryong, to play for dances. In the 1960s, he joined with his friend Con Klippel in the Klippel family's band and dance activities in the Nariel Valley. Peter Ellis relates that he "was a showman on the concertina, and could play a cossack-type dance (frog dance) on his haunches whilst playing, and in fact one night pulled the instrument in half."![]() 10> He also enjoyed swinging the concertina around, windmill fashion, for the effect on the instrument's tone. Harrison's repertoire was rich in waltzes, polkas, mazurkas, varsovianas, and set dance tunes, as well as songs. He played mostly button accordion player in his later years, but in a field recording made by Peter Ellis and Ian Simpson in 1982, he played the German concertina of his youth. By this time, he was many years out of practice, and what is preserved is in no way a recording of him at his best. The National Library of Australia has made these recordings available for this collection.

10> He also enjoyed swinging the concertina around, windmill fashion, for the effect on the instrument's tone. Harrison's repertoire was rich in waltzes, polkas, mazurkas, varsovianas, and set dance tunes, as well as songs. He played mostly button accordion player in his later years, but in a field recording made by Peter Ellis and Ian Simpson in 1982, he played the German concertina of his youth. By this time, he was many years out of practice, and what is preserved is in no way a recording of him at his best. The National Library of Australia has made these recordings available for this collection.

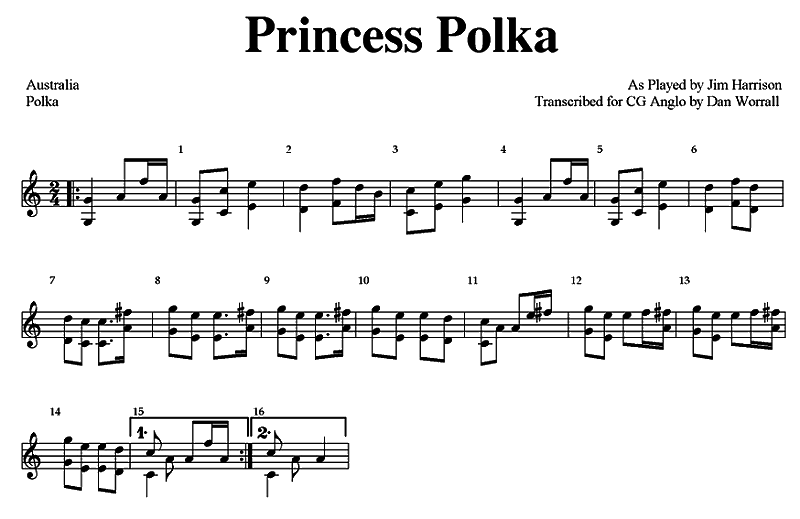

One of his dance tunes, Princess Polka, provides a good example of his playing technique. Like other Australian players, Harrison plays in octaves. The tune is in C, and the A part is played entirely on the C row. Harrison freely dropped octave notes when difficulties - either in the form of extra low notes or notes with fast transitions - were met, as in measures one, three, and five. The B part moves back and forth from the C to the G row. Like Chapman, Harrison frequently used a dissonant F#, even though the tune itself is in C.

An Untitled schottische is played in the key of C, in octaves and all on the C row.

The Mill Belongs to Sandy is a single reel which Harrison plays in the same fashion: in the key of C, in octaves and all on the C row.

In his later years, Harrison was considerably more practiced at playing the button accordion; the switch to accordion had been the end of many a concertina player of his era. In Why Did My Master Sell Me he plays with Neville Simpson of the Nariel area. This particular tune is an old American abolitionist tune, spread by the minstrels by at least the early 1850s. This tune is very commonly known and played in present day Australia.

Charlie Ordish, with German concertina,

at a Nariel Valley music gathering in the 1960s.

With thanks to Peter Ellis and Dave de Santi.

Ordish was recorded informally with Jim Harrison and Con Klippel in the 1960s; the recording is in the Norm O'Connor collection at the National Library of Australia, and the Library kindly made them available for this archive.

So Early in the Morning is a popular Australian polka of probably American origin, and Charlie plays it on his CG German concertina. It is played in the key of C, entirely on the C row, as are all his recorded pieces. He appears to have been strongly influenced by the one-row C accordions used in the Nariel area.

The Irish jig St Patrick's Day in the Morning is also played in the key of C, and all on the C row. It is played at a sprightly pace, and only about half in octaves as a result, and with a few end-of-phrase chords. He only plays the A part. A recording of the same tune by Englishman Scan Tester is included in Chapter 9, below.

An Untitled Polka Mazurka is played at a slower tempo, all in octaves on the C row, and in the key of C. Several polka mazurkas were played by the Nariel band through the years, and this one is similar to the one they called Little Children.![]() 13

13

A varsoviana used in the Nariel band called Turn Around and Then Stop, is played in the key of C, again all on the C row in octaves.

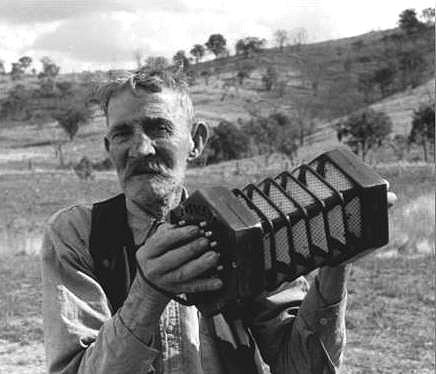

Fred Holland, of Mudgee New South Wales, with his John Stanley concertina, 1957.

He is demonstrating the old practice of waving the concertina

for emphasis during the playing of dance tunes.

Photograph by John Meredith, in the archives of the National Library of Australia.

According to John Meredith, Holland lived in a particularly inaccessible valley set in steep hills, an area still without electricity in the 1950s. He was recorded at the very advanced age of 88 and with a concertina that is clearly in need of a tune. These field recordings hardly do Holland's playing justice, but they are all we have of this well-known and respected musician. They have been made available by the National Library of Australia.

The existing recordings, made by Meredith in 1957, record a sparse playing style with few ornaments, accented mainly by frequent octave notes and only an occasional chord. The first two tunes below are pitched in the key of Ab on the recordings. This seems to be an artifact of the tape recordings - some sort of pitch wobble caused by the current inverter that was used to power the tape recorder, from the battery of a Land Rover (Meredith later began using a tuning fork at the beginning of recordings, to avoid such problems). Holland's house had no electricity at the time of Meredith's visit. It is likely that his concertina was pitched either in Bb/F or C/G.

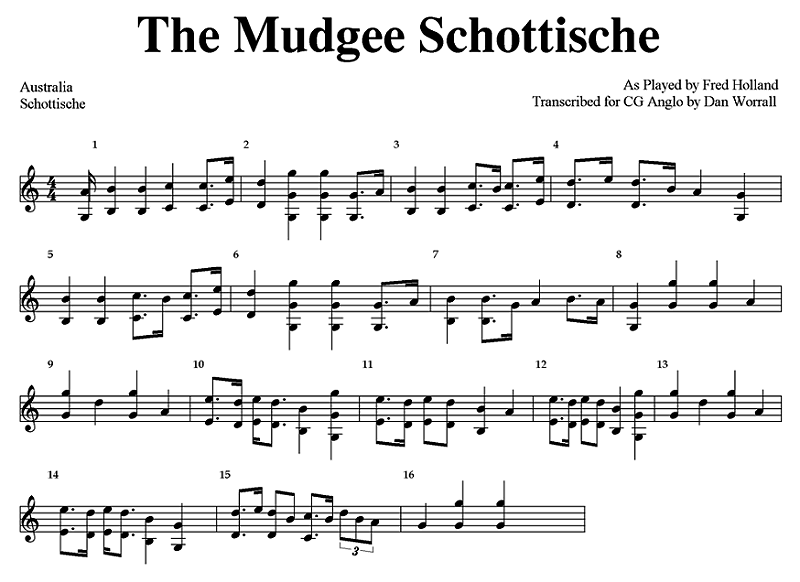

In the following transcription the Mudgee Schottische is transposed to the key of C, which fits the pitch of concertinas owned by most players today. The tune is played mostly on the C row, with occasional brief ventures onto the G row. Holland played nearly entirely in octaves, like most other old time players in Australia who were recorded. It should be noted that the entire A part is reasonably easily played on the G row, an octave up, but clearly that was not Holland's preference.

Fred Holland's Mudgee Schottische. Transcribed for C/G Anglo by Dan Worrall.

An Untitled Schottische is played similarly in the key of Ab on the tape recording (again, probably actually Bb or C).

Write Me a Letter Home was one of the popular hits of 1866, and was written by the American poet and lyricist William Shakespeare Hays. Many of Hays' songs and tunes were spread by the minstrel shows, and he claimed to be the author of Dixie (a claim in dispute, as most consider it the work of Dan Emmett). Write Me a Letter Home is played by Holland in the key of C# on the tape, clearly the problem of the wobbling pitch of the tape recorder used.

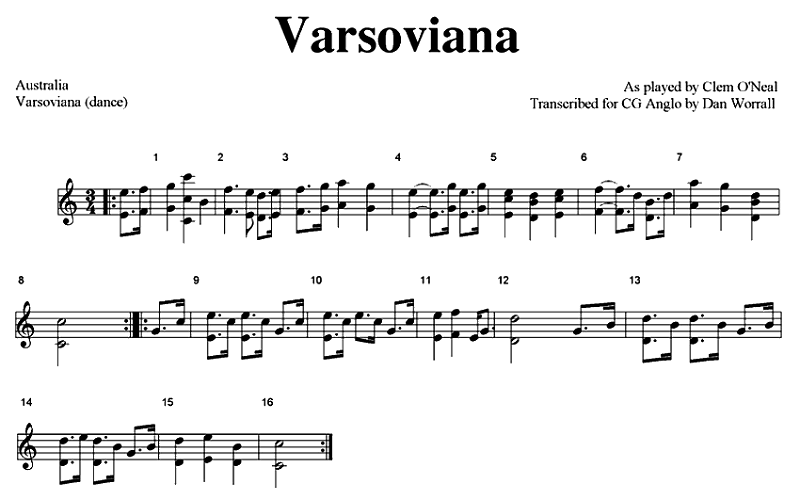

Clem O'Neal, at an Irish session in Sydney, 1977. O'Neal emerged into the Australian folk

revival scene in the 1970s unaware that other Australian concertina players still existed.

When Dave de Hugard, an Australian-style Anglo player took him to this Irish session,

he said that he liked it but that he "never heard anything like that where I am from."

With thanks to Dave de Hugard.

Both O'Neal's father and grandfather were also born in Iron Bark; his great-grandfather seems to have come to Australia after the Wicklow rebellion in Ireland, in 1828. Clem O'Neal learned the concertina at the age of ten, after an unsuccessful stint on the violin. His first instrument was a 20-keyed German concertina, but he later played Lachenal Anglo-German concertinas. According to O'Neal, the primary source of new tunes in his younger days was from people returning from trips, and the modifications of the 'folk' process started then:

Varsoviana (Kick Your Leg Up, Sal Brown) was a nearly universally known tune in O'Neal's younger days, and is still known among musicians and dancers in England, Ireland, and the United States (a version by George Bennett is included above). O'Neal plays it completely on the C row of a C/G concertina, partly in octaves (note: the cassette recording is about 30 cents sharp).

Clem O'Neal had a number of schottisches; here are three. The Untitled Schottische is played on a CG Anglo, in the key of C, and like the above varsoviana, it is played entirely on the C row. He was mostly a single-row player, and lamented the fact that he did not learn how to cross-row like other Australian players. He tended to play octave notes rather sparingly, as accents, and added the odd chord at ends of phrases. North Wind Schottische are recorded on a cassette player that is off-pitch (one semitone sharp); he appears to be playing both of them in G, all on the G row of a GD concertina. The North Wind was a globally popular tune, and was recorded by American accordionist Myron Floren, among others.

All By Yourself in the Moonlight is a barndance tune (schottische rhythm) played on a G/D concertina, in the G row in G (the cassette tape is one semitone sharp). It is a British music hall song, written by Ralph Butler (his pseudonym was Jay Wallis) in about 1928. Peter Ellis considers it one of the best barndance tunes, because it helps emphasize for dancers the pause and kick at the end of each relevant bar in the song. Here is the first verse:

The Boston Two-Step, despite its title, is an English dance composed by Tom Walton in 1908. Clem O'Neal's version is fairly close to the dance's signature tune. A variant of the two-step, it is danced to this day in Ireland and Australia.

Susan Colley, holding her grandchild,

and standing next to her daughters.

Photo courtesy of Warren Fahey.

Duramana's heyday as a pastoral village was in the late nineteenth century. Gresser described the village's dances:

Susan Colley's repertoire of dance tunes primarily consisted of waltzes, mazurkas, polkas, and varsovianas, as well as tunes for set dances - quadrilles like the Lancers and the Alberts. As befits that of most Australian players, her style was melodic and sparsely (if at all) ornamented by grace notes; she played for the dance. She used frequent octave notes for emphasis and volume, and in doing this she often substituted a note a third up from the lower octave, which gave a harmony to her playing. She did not often use full chords.

Susan Colley was recorded by Warren Fahey in 1973, when she was living in an old age home in Bathurst. She was 92 years old at that time. Warren has kindly made several recordings available to this archive. In the first, she describes the old dances to Fahey.

Her Varsoviana tune is a distant variant of the one played by Clem O'Neal in the previous section. Its apparent key on the recording is E, but it is likely that the tape is sharp and that she played it in D on a G/D instrument. It is played all on the D row, largely with octaves and with many partial chords.

The Wild Colonial Boy, is a traditional Australian ballad about an Irish rebel who became a bushranger. Like Bennett's song about Ned Kelly, in an above section, this ballad sympathizes with the Irish-Australian outlaw.

Ernie James (right), at Home Rule, New South Wales, in 1957.

Photo by John Meredith, courtesy the National Library of Australia.

James was recorded in 1974 by Bruce Kurtz and his father, Reg Kurtz. The tapes were given to John Meredith and are housed at the National Library of Australia. Bruce Kurtz and the National Library have made them available for this collection.

Ernie James played an old German concertina, and knew a variety of dance tunes and old songs. The Berlin Polka is one of many dance variants of the polka. In Australia, a version of this dance was collected by Shirley Andrews in Nariel, but to a different tune and dance than that played by Ernie James here. James version is played for a 'Kreuz' form of that polka, and is a fine tune. The tape appears to be about a semitone sharp. If that is correct, James plays it in the key of G on a C/G Anglo concertina. He played much of the tune in octaves. James was a skilled cross row player, and such playing is evident in all of his recorded tunes.

The Bullfrog Hop is a form of two-step played in jig tempo, and is played by James in the key of G, largely in octaves. Frank Bourke (1923-1989) of Binnaway, New South Wales claimed to have written the tune, and it worked its way into the local dance repertoire.

An Untitled Schottische is played in G on a C/G concertina, largely in octaves and in a cross-row manner.

The Cornflower Waltz was written by American Charles Coote around 1879. It is played on a G/D German concertina, in the key of D. Like all of James's tunes, it is played in cross-row manner and largely in octaves, with a few phrase-ending chords.

Percy Yarnold in 1985, playing his German concertina.

Photo by John Meredith, courtesy the National Library of Australia.

All of Yarnold's recordings were made by Meredith in that 1985 visit, and are included here courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

Claude Keightley was a bullock driver and Anglo concertina player; Yarnold began playing with him in 1917. In the first track, Yarnold describes playing with Keightley, and then plays Keightley's Schottische. He played a baritone C/G German concertina that had two sets of reeds and sounds like a button accordion as a result. Yarnold plays this piece in C, modulating to G on the B part. A skilled cross-row player, he played this tune on both rows.

Here Yarnold discusses the dances that they played for.

Early in the Morning is a widely known Australian polka. It is played in the key of C, and nearly entirely in octaves. It is played mostly on the C row, except for a few high notes on the B part.

The Woolly Tail Foxtrot is played in C, in octaves, and in a cross-row fashion. The foxtrot was introduced in the 1920s, one of a number of progressive (sequence) dances of that era.

2. C H S Matthews, A Parson in the Australian Bush (London: Edwin Arnold, 1908), pp.113-114.

3. Dooley Chapman, Your Good Self, CD, Chris Sullivan's Australian Folk Masters, CS-AFM-001, 2005,

4. see Lucy Stockdale, Obituary, Shirley Andrews, OAM: at the online website Australian Folk Songs, www.folkstream.com.

5. Dooley Chapman, Your Good Self, CD, Chris Sullivan's Australian Folk Masters, CS-AFM-001, 2005, Also see Chris Sullivan, 1983, Albert 'Dooley' Chapman, Australian Concertina Player: Concertina Magazine, Number 3, pp.7-11.

6. Dooley Chapman, Your Good Self, CD, (2005).

7. Ibid.

8. 'The Kelly Gang', Marlborough Express (New Zealand), July 21, 1880, p.2.

9. Peter Ellis, personal communication, 2011.

10. Peter Ellis and Harry Gardner, Music Makes Me Smile, (1998), p.12. The biographical sketch of Harrison is drawn completely from this source, pp.28-29.

11. Ray Simpson, in a personal note to Peter Ellis, 2009.

12. Peter Ellis and Harry Gardner, 1998, Music Makes Me Smile: Carrawobitty Press, Albion Park, NSW, p.12.

13. Peter Ellis and Harry Gardner, 1998, p.126.

14. John Meredith, Folk Songs of Australia, (1967), pp.227-232. Also Bruce Kurtz, 1985, Fred Holland, Concertina Player from the Past: Concertina Magazine, No. 11. pp.7-9.

15. 'Clem O'Neal, Anglo Player', Richard Evans, ed., Concertina Magazine, Winter 1982, pp.7-10.

16. Percy J Gresser, 1965, The Songs They Sang - and - the Dance Tunes They Played: Copies of Gresser's extensive manuscript and songs recorded from Mrs. Colley were sent to the archives of the Bush Music Club of Sydney, as well as to the Wild Colonial Days Society of New South Wales. I am grateful to Bob Bolton for a copy of this work.

17. Ibid., pp.51-52.

18. John Meredith, 1995, Real Folk: The National Library of Australia, Canberra, p.19.

| NEXT |