The 'original' tunes for each new dance were usually based on the style of the tune of the original folk or national dance; many of these became globally known. The universal varsoviana tune highlighted at the end of Chapter 4, Put Your Little Foot/Shoe the Donkey/Kick Your Leg Up Sal Brown, is a good example of such a 'global' tune. In places like England and Ireland where the varsoviana dance faded with time, only this original version is still remembered in the folk tradition. In Australia, where the dance lingered until the present day in the rural bush, there are many different versions of varsoviana tunes known among traditional musicians. This longevity of varsoviana dancing allowed time for local variations of the original tune to mutate, and for completely original versions to be composed. Some of these versions, like George Bennett's varsoviana in Chapter 4, above, are partly to largely similar to the original tune. Others, like Charlie Ordish's varsoviana tune (also in Chapter 4), seem completely new, and different.

Clem O'Neal described the process by which such tunes mutated in the Australian bush. According to O'Neal, the primary source of new tunes in his younger days was from people returning from trips, and the modifications of the 'folk' process started then:

The global nature of much of this dance music is not always apparent today. Sussex musician Scan Tester (1887-1972), and Dooley Chapman (1892-1982) of New South Wales, were both rural working class men who played professionally for dances. Both held high stature amongst traditional musicians in their day, but neither travelled outside of their home continent. In their youth there was little or no radio, and they were separated by twelve thousand miles of ocean. Nonetheless, both share an obscure polka tune to which neither could ascribe a title. Here is Dooley Chapman's version of this untitled polka; the recording is courtesy of Chris Sullivan.

And here is Scan Tester's version of the same untitled polka; the recording was made by Reg Hall and is courtesy of Topic Records.

Most likely, this polka was once popular, perhaps with its own signature steps, but one that has faded a century later. It has affinities in its A part with the Irish song Bog Down in the Valley, and with the tune that accompanies the old Thomas Moore poem Oft in the Stilly Night, but it varies significantly in the B part relative to both of these.

George Bennett also played All Smiles Tonight, which was written by American T B Ranson in 1879 and popularized in country and western recordings of the early twentieth century. All Smiles Tonight also made it into South Africa, where Boer concertina players know it as Die Kalfie Wals (The Calf Waltz). The recording is courtesy of the National Library of Australia

In South Africa, Faan Harris (1886-1950) recorded the popular Wals van Tant Sannie (Aunt Sannie's Waltz) in the 1930s; it is a rename of the Shannon Waltz, an American tune first recorded in the 1920s by the East Texas Serenaders, and was taken from an itinerant fiddler known only as Mr Briggs. The recording of Harris and Die Vier Transvalers is courtesy of Die Tradisionele Boeremusiekklub van S.A.

Another yet more global nineteenth century song is the Irish-American sentimental song Eileen Alannah, composed in 1873 by American composer John Rogers Thomas. In South Africa, a beautiful recording of Eileen Alannah was made by Faan Harris and Die Vier Transvalers in the 1930s. The recording is courtesy of Die Tradisionele Boeremusiekklub van S.A. This song was popularized by Irish tenor John McCormack, and the tune found its way into the 1929 Roche Collection of Traditional Irish Music as an old time waltz. In Britain, it became the slow regimental march of the Royal Innskilling Fusiliers, now the Royal Irish Rangers, and was popularized in this century by accordionist Jimmy Shand. In Australia, it was a popular old time waltz played by Con Klippel and others in the Nariel Valley, and found its way into the book of Nariel traditional dance music, Music Makes Me Smile.![]() 39

39

Another American hit tune that was popular with concertina players on several continents was Two Little Girls in Blue, written in 1893 by American composer Charles Graham and re-used for a 1921 Broadway musical comedy of that name, and here played by George Bennett. In Sussex, Scan Tester played the tune with his Tester's Imperial Jazz Band, and during the English Country Music surge of the 1970s it was again recorded by the English band Flowers and Frolics. In Australia, Two Little Girls in Blue was part of George Bennett's repertoire: this recording of his version is courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

British Music Hall hits also had legs. The 1928 song, Starry Night Waltz, also seems to have originated in the London halls, and is first known from a broadsheet published there in 1854.

Harry Thompson, a popular performer in the British Music Hall,

with Anglo-German concertina, 1909. Thompson appeared

under the stage name Harry Tomps and was the father of concertinist

and Music Hall performer Peter Honri. From Percy Honri's Working the Halls, 1973.

Such tunes were despised by the Gaelic League, which had much loftier (and more nationalistic) cultural goals. A 1908 member had this to say of Ireland, the concertina and the Irish peasant:

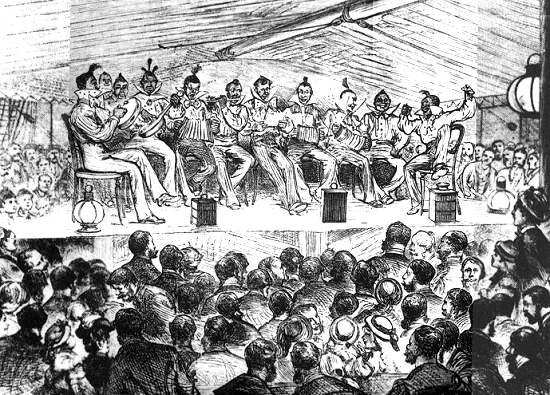

A blackface minstrel show in London, late nineteenth century.

Such shows were rowdy, musically varied, and hugely popular for decades around the globe.

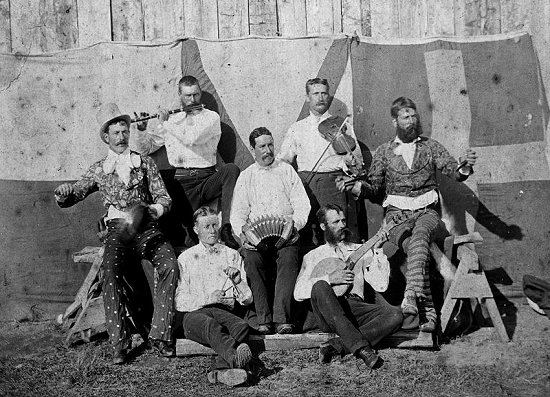

Soldiers in a 'Christy minstrel' group, Opunake New Zealand, 1876.

Note the 'end men' in garish garb; these were the jokesters of the show.

Also note the central placement of the musician with the German concertina.

Some of the tunes played by concertina players in this archive have titles that clearly identify them as minstrel tunes. Dooley Chapman (1892-1982) of Coborrah, New South Wales Australia, played Old Dan Tucker, a comic minstrel tune with words reportedly written by early minstrel leader Dan Emmett (the recording is courtesy of Chris Sullivan). An instant hit after its introduction in 1843 by Emmett's Virginia Minstrels, it tells the story of a black man who finds himself in a strange town, fighting and getting drunk. The tune that Dooley Chapman plays has morphed a bit since leaving America, but was commonly played in Australia; George Bennett played a similar tune called Old Man Tucker.

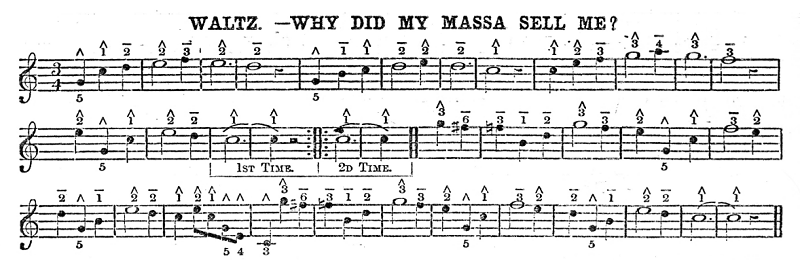

The origin of other minstrel tunes has been hidden by the addition of new titles at some point in their history. Such seems also to be the case with present-day Clare concertina player Chris Droney's version of The Blue Gentian Waltz, which he played on a Free Reed records release of 1974, The Flowing Tide. This waltz seems to have been learned from Chris Droney's father, Jim Droney, whose music is featured in Chapter 9 of this archive. The Blue Gentian is the name of an Irish wildflower, but that may not have been the first title of this waltz. The tune is nearly identical in its 'A' part to a tune very popular in Australia among traditional musicians, Why Did My Master Sell Me. This version is from Jim Harrison (1911-c.2000) of Khancoban, New South Wales, on concertina, playing with Neville Simpson on accordion. It was recorded in 1982; courtesy of the National Library of Australia. The tune was tune was originally a popular American abolitionist tune about the evils of slavery, which was appropriated as a tear-jerker by the minstrel shows and as a hymn-tune by the Salvationists. The original song was written at least by 1852, because Catherine Booth (Herbert Booth's mother) wrote about hearing it sung in the streets of London that year.

Oh! I have lost my Dinah, away down Carolina,

O, tell me where to find her, Alas! she's gone away.

My master he does scourge me, and oft to work does urge me,

And Dinah's freedom forg'd he, upon our wedding day.

Chorus:

O, why did my master sell me? Why did master sell me?

Why did master sell me, Upon my wedding day?![]() 41

41

A number of traditional musicians in Australia were recorded playing this song, and it became a popular waltz tune.

Sheet music for Why Did My Massa Sell Me?, an American abolitionist song,

from Dance Music for the Concertina, published in Glasgow in 1864.

The song was spread by the minstrel shows and found its way to some far corners of the world.

The most universally known of the minstrel tunes among concertina players were those of Stephen Foster. Some of the song tunes spread by the minstrel shows (which are included in dozens of nineteenth century concertina tutors and tune books published in Britain and the USA) include The Old Folks at Home, Camptown Races, Oh Susannah!, Beautiful Dreamer, Old Black Joe, and Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair. It is perhaps safe to say that nearly all concertina players in late nineteenth century England, Australia and Ireland could play, hum or sing many if not all of these tunes. Susan Colley (1881-1976), a singer and concertina player of rural Duramana New South Wales, could sing all of these as well as other minstrel favorites like Nellie Grey, Lily Dale, Massa's in de Cold Cold Ground, Old Kentucky Home, and I'se Going Back to Dixie.![]() 42

42

In England, good social dance tunes were always in high demand for morris dancing, and minstrel shows provided a wealth of possibilities. In Lancashire, the village of Royton's morris team used Stephen Foster's minstrel tune Oh Susannah. Ellis Marshall (1906-1993) and fellow concertina player Norman Coleman, along with some drummers, played for the Royton men's morris team at an exhibition dance at the St Paul's Working Men's Institute in 1979, using a medley of tunes they had played in previous decades with the side. The medley included bits of Foster's Oh, Susannah, as well as the traditional English single reel Brighton Camp (aka The Girl I Left Behind Me), as well as a Cross-Morris dance tune. The recording is courtesy of Ellis's grandson, Tony Marshall.

At nearby Manley, concertina player Caleb Walker also used Oh, Susannah! for the local morris, although he called it Banjo on My Knee: "It's a good tune - nearly all those American tunes fit - you could pick half a dozen out that'd fit it a treat."![]() 43 In Headington Quarry, Oxfordshire, William Kimber (1872-1961) played Getting Upstairs for the Headington Quarry side. It was recorded by Kimber in 1935, and is courtesy of the English Folk Dance and Song Society. American Joe Blackburn wrote this tune for blackface minstrelsy in the 1830s and published it under the title Such a Getting Upstairs.

43 In Headington Quarry, Oxfordshire, William Kimber (1872-1961) played Getting Upstairs for the Headington Quarry side. It was recorded by Kimber in 1935, and is courtesy of the English Folk Dance and Song Society. American Joe Blackburn wrote this tune for blackface minstrelsy in the 1830s and published it under the title Such a Getting Upstairs.![]() 44 It is not clear that folk music and dance collector Cecil Sharp realized that Getting Upstairs was a former minstrel tune when he noted the tune and accompanying dance, and included it in his 1919 collection of classic English morris dances.

44 It is not clear that folk music and dance collector Cecil Sharp realized that Getting Upstairs was a former minstrel tune when he noted the tune and accompanying dance, and included it in his 1919 collection of classic English morris dances.

39. Peter Ellis and Harry Gardiner, 1998, Music Makes Me Smile: a Tribute to Con Klippel and the Music of the Nariel Valley: Carrawobbity Press, Albion Park NSW, 228p.

40. The Anglo-Celt (Cavan), April 18, 1908.

41. From an 1850s broadsheet, for sale on an internet site.

42. Percy J Gresser, 1965, The Songs They Sang - and - the Dance Tunes They Played. Copies of Gresser's extensive manuscript and list of songs recorded from Mrs Colley were sent to the archives of the Bush Music Club of Sydney, as well as to the Wild Colonial Days Society of New South Wales. I am grateful to Bob Bolton for a copy of this work.

43. Derek Schofield, 'Concertina Caleb', (1970s).

44. Rhett Krause, 'Morris Dancing and America Prior to 1913', American Morris Newsletter 25, no.4, (2005).

| NEXT |