FOUR VICTORIAN VIEWS

Allan W. Atlas

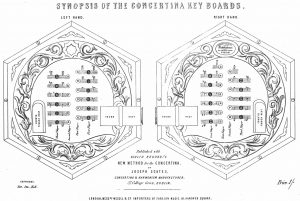

To get us started, Figure 1 shows the layout of the English concertina’s button boards, and should prove helpful to players of other systems.

Fig.1. “Synopsis of the Concertina Keyboard” (after Giulio Regondi, New Method for the Concertina [Dublin: Scates/London: Wessel, 1857], frontispiece).

Thus there are four vertical rows. Starting with the row closest to the thumb straps: row 1 contains what are black keys on the on the piano and is covered by finger 1 (index finger); rows 2 and 3 have the white notes and are covered by the first and second (middle) fingers, respectively, so that finger 1 does double duty on rows 1 and 2; row 4 once again has black keys only and is covered by the third (ring) finger, while finger 4 (little finger) has its designated “rest[ing]” place. Within each row the buttons are a 5th (of one kind or another – perfect, augmented, diminished, and even doubly diminished) apart from one another.

Finally, Victorian method books sometimes turned the instrument on its side and visualized the vertical rows as being horizontal. They dubbed them: row 1 = “upper black”; rows 2 – 3 = “upper and lower white”; row 4 = “lower black.”

* * * * *

Even a cursory glance at late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century method books for the English concertina shows that the fourth finger remains in the finger rest provided for it and helps bear the weight of the instrument. This is certainly true in tutors by Alistair Anderson, Frank Butler, Pauline De Snoo, Wim Wakker, and my own contribution to the literature, none of which — either verbally or through music examples — ever calls for that finger to play even a single note. 1 I know of only one tutor from this period that dissents even slightly, that by Alf Edwards, who writes:

For the two middle rows (two and three) use the first and second fingers. The first finger which naturally plays the second row must also be used to play the first row . . .

The fourth row is played by the third finger. Alternative fingering – using the fourth (or little finger) will be dealt with later. 2

In fact, Edwards does not “deal” with (in the sense of discussing the use of) the fourth finger at all. Instead he merely calls for it to be used sparingly in the course of three exercises (Ex. 1).

Ex. 1. Edwards, Wheatstone’s Instructions: (a) p. 44, no. 8, meas. 14-17;

(b) p. 46, no. 5, meas. 5-6; (c) p. 51, no. 6, meas. 1-3.

What I find striking about Edwards’s fingerings is this: his use of the fourth finger seems entirely non-essential; there is not one instance in which finger 3 of the right hand would not have done the trick just as well (though Example 1a would require that finger to play two notes in succession — g’’ to f’ sharp — something that, as we will see, the Victorians tried to avoid). In a way, Edwards himself seems to acknowledge this: after using the fourth finger on the b flat in Example 1c, measure 2, he calls for the third finger on the very same note (and in conjunction with the same b flat/g dyad) in measure 3, with no good reason for the change coming to mind.

* * * * *

The Victorian period offers a rather different picture, one in which finger 4 often played an important — at times even indispensable — role. Yet I wonder if we sometimes overestimate its ubiquity, for opinions about the use of the fourth finger were hardly one-size-fits-all, and not all players used — or were expected to use — it. What follows looks closely at ten Victorian method books for the English concertina, and shows that they expressed four rather different views on the matter. These might be categorized (somewhat roughly) as follows: (1) use finger 4 whenever necessary, which category I would call the “mainstream”; (2) use it — dogmatically so — even when it’s not necessary; (3) a skeptic’s voice about the use of finger 4; and (4) the fourth finger remains in its finger rest.

(1) The “mainstream”: We might describe the most widespread (perhaps even the most “authoritative”) view about the use of the fourth finger as follows: use it freely and whenever necessary, but not in a manner that is either rigid or dogmatic. This is the view advocated by Giulio Regondi, Richard Blagrove, Joseph Warren (his “New System” aside for the moment – see below), and Alfred Sedgwick. 3 Blagrove writes as follows about the most basic “rules” of fingering:

1st Finger belongs to the 2nd Row.

2nd Finger ” ” ” 3rd Row.

3rd Finger ” ” ” 4th Row.

The first finger which naturally belongs to the second row

must be moved from the second to the first row when required.

He quickly adds, however: “The little finger should be used whenever it will simplify the fingering. It will be found very important in the 6ths, 8ths and 10ths in the sharp and flat keys” (Instruction Book, p. 4).

Writing a few years before Blagrove, Regondi had offered the following, somewhat more nuanced, prescription:

The fourth finger plates or holders . . . are useful to beginners in order to balance

the hands . . . but in a more advanced stage and when the power has been acquired

of playing the full and extended combinations of notes now prevailing in Concertina

music, it is impossible to dispense with the use of the fourth finger if any regard be

had to a proper mode of fingering (New Method, p. 6).

And if Regondi distinguishes between beginners and players at a more “advanced stage,” Joseph Warren draws an even starker distinction:

. . . with practice, [the fourth finger is] capable of being made very useful in facilitating

some passages and chords, and preparing others. It is used more or less by the professors

of the instrument; but it has not as yet [1852] been brought into general use . . .

(Complete Instructions, p. 6). 4

The picture, then, seems clear enough: though mid-Victorian practice advocated the liberal use of the fourth finger, it recommended the finger only to those who were already somewhat advanced or, even more narrowly, to the “professors,” that is, to the teachers of and professional performers on the instrument.

Yet before looking at the various circumstances under which finger 4 was used, we should come to terms with what Regondi calls the “proper mode of fingering.” The Victorians seem to have had three cardinal rules (“of thumb” – since they could all be broken when necessary), two of which (items b and c below) had an impact on when the fourth finger was called into play.

(a) When playing two successive notes in the second vertical row of either hand, the Victorian default (whether ascending or descending, and even if the notes were more than one button away from one another) was to use finger 1 on the bottom note, finger 2 on the upper note. 5

(b) One should avoid playing two successive notes with the same finger. As George Case puts it:

The rule regulating good fingering is, to avoid as much as possible using the same

finger for two successive notes, or lifting a finger off one note to play another in

immediate succession. 6

(c) When a passage calls for G sharp, D sharp, A flat, or E flat, one should play those notes precisely as “spelled,” that is, with the sharp or flat button that is adjacent to its natural cousin. Blagrove writes:

The student will notice that the Concertina possesses the peculiarity of having

separate notes for G sharp and A flat; D sharp and E flat; the extra notes simplify

the fingering and he should therefore when D or G sharp are required play the notes

next to D and G natural, and when A or E flat are required play those next to A and

E natural (Instruction Book, p. 29).

Thus our mid-nineteenth-century method books agree on the following fingering for a chromatic scale.

Ex. 2. A one-octave segment of a chromatic scale in Blagrove, Instruction Book, p. 29;

Blagrove takes the scale up to c’’’’ and then descends back to the starting note;

asterisks indicate where an enharmonic note would become available on an equal-

tempered instrument (see below).

That neither Blagrove nor any of the other authors of mid-century method books ever calls for an enharmonic equivalent (for example, an e’ flat with finger 3 in the left hand in place of the d’ sharp and finger 1 in the right hand) points to their having had a meantone concertina in mind, one, therefore, without enharmonic equivalents, something that, I think, will have important implications for the way they used the fourth finger (see below).

Under what circumstances, then, did Regondi, say, call finger 4 into action? Example 3, which draws upon both his New Method and his Rudimenti, illustrates four such instances: to manage large stretches that would otherwise be cumbersome (Ex. 3a); to avoid having to use the same finger on two successive notes (Ex. 3b); to negotiate complex two- and/or three- part writing (Ex. 3c); and to deal with thick, widely-spaced chords (Ex. 3d).

Ex. 3. Regondi, four circumstances that call for the use of finger 4: (a) New Method,

p. 24, no. 5, meas. 1-2 (the bracketed fingering is editorial); (b) New Method, p. 17,

where the chromatic 3rds appear as 8th notes under the time signature C; (c) New

Method, p. 50, no. 9, meas. 1; (d) Rudimenti, p. 23, “Harmonized Minor Scales in

3 Gradations,” no. 3, meas. 4 (fingering for left and right hands shown before and

after the note heads, respectively).

Discussion:

Ex. 4a – Two points: (1) we can “narrow” the stretch between the low d’ and the high f’’’ a bit (and thus do without finger 4) by using the first finger on the upper note, thus permitting the use of finger 3 on the low d’; this, however, would rub against the “rule” that prohibits using the same finger on two successive notes, since finger 1 in the right hand had been tied up on the sustained e’’ flat; (2) we could get around the latter problem by substituting the left hand’s d’’ sharp (for the e’’ flat), though that would run up against the preference for playing things as they are spelled as well as sounding out of tune in the key of E-flat major on a meantone instrument.

Ex. 4b – Even with the use of enharmonic equivalents (a flat in the left hand in place of g sharp in the right hand on the second third), there is no way to get even as far as the fourth 3rd without having to use the first finger on both c’ and then on c’ sharp. The fourth finger is absolutely necessary if the chromatic thirds are to be played legato. 7

Ex. 4c – We can substitute left hand fingers 3 and 2 (for Regondi’s 4 and 3) on the sustained a and e’, but only if we then use e’’ flat for the notated d’’ sharp in the second and third groups of 16th notes. Question: is it possible that there is a dot missing after the a, which would require that it be sustained through the entire measure? In that case the first suggestion will not work.

Ex. 4d – Regondi proudly writes as follows about such monster chords:

Chords of eight notes are easy because by releasing the little fingers from their

holders . . . the player has then eight fingers at his disposal; and it is possible to

put down two or even three keys with the same finger and thus to increase the

number of notes in certain chords (New Method, p. 1)

In fact, in his Rudimenti (p. 17), Regondi calls for a chord with fourteen notes.

Although Regondi, Blagrove, and Sedgwick all advocated the use of the fourth finger, they did not always see eye to eye about just when to use it. Example 4 shows that they disagreed on how to finger a descending E-major scale played in 6ths (the one-octave descent is all that Sedgwick offers).

Ex. 4. Descending E-major scale in 6ths: (a) Regondi, Rudimenti, p. 11;

(b) Blagrove, Instruction Book, p. 26; (c) Sedgwick Complete System

of Instructions, p. 4; note that I give only as much of Regondi and

Blagrove as matches the portion provided by Sedgwick, and that I

provide non-rhythmic note heads for the eighth notes in Blagrove

and Sedgwick and the quarters in Regondi.

There is not a single instance in which all three method books agree, with some of Sedgwick’s fingering — I am thinking of the 6ths on d’ sharp/b’ (2nd finger on d’ sharp), c’ sharp/a’ (3rd finger on c’ sharp), and g sharp/e’ (2nd finger on g sharp) — being downright bizarre.

Finally, there is a question (already briefly alluded to) that has been simmering on a back burner throughout this discussion: why do the method books (at least those at which I’ve looked) insist on “play-it-as-spelled,” that is, a notated D sharp with the button next to D natural, a notated A flat with that next to A natural and so on? Why do they never mention the possibility of using an enharmonic equivalent: for example, an E-flat button instead of that for D sharp? As hinted at above, and to state once again some thoughts that I offered in my Introduction to Blagrove’s Instruction Book (see note 4), I would argue that it is because the concertinas for which Regondi, Blagrove, Case, Warren, and other mid-century authors of method books were writing did not yet offer such enharmonic equivalents, that they were still dealing with instruments that were tuned to Wheatstone’s original meantone tuning in which the octave was divided into fourteen parts, with the E flat and A flat tuned forty-one cents higher than the D sharp and G sharp, respectively (note that an equal-tempered half step is a hundred cents), and that to substitute, say a g sharp for an a flat would have resulted in the music being out of tune. Thus I would suggest that the use of the fourth finger might sometimes (perhaps even often) have been necessary because the player had no enharmonic equivalent that would have obviated the need for it.

Two examples of such a possibility from Blagrove’s transcription of the “Cujus animam” from Rossini’s Stabat mater will suffice (Ex. 5).

Ex. 5. Blagrove, Instruction Book, pp. 33, 35, transcription of the “Cujus animam”

from Rossini’s Stabat mater: (a) meas. 48 – x = with finger 4 as called for by

Blagrove, y = alternative fingering with enharmonic equivalent and without finger 4;

(b) meas. 100 – x = with finger 4 as called for by Blagrove, y and z = two alternative

fingerings with enharmonic equivalents and without finger 4.

Thus at measure 48, we may simply substitute the e’ flat (left hand) for Blagrove’s d’ sharp (right hand), while at measure 100, we can avoid using the fourth finger either by using a d’ sharp for the e’ flat or by replacing the high a’’ flat (left hand) with a g’’ sharp (right hand). Clearly, these substitutions can be made only on an equal-tempered instrument. 8

We will consider the other three views more briefly.

(2) Warren’s “New System” – row 4 = finger 4: Having initially relegated the fourth finger to the realm of the “professors” and stating that “it has not as yet been brought into general use” (see above), Joseph Warren then did a 180-degree about face (in the very same paragraph):

. . . some exercises have been added, as an appendix, to show the utility of using

the fourth finger generally; and it will be seen that the principle is to use one

finger for each row of stops; the first [finger] for the upper black row, the second

and third for the upper and lower white rows [the two middle rows], and the fourth

finger for the lower black row. The natural scale [C major] is fingered by alternately

using the second and third fingers of each hand . . . In the scales of Eb, Bb, and G, D,

A, and E, the first finger has to be used for the upper black row, and the fourth for the

lower black row of stops; the first and fourth fingers being only used in their respective

rows, when the particular note has to be made sharp or flat. When accidental notes occur,

or a chromatic scale has to be played, the fingers are all ready to be pressed down without

disturbing their position. By this means the fingering in the scales is considerably

simplified, as every note can be prepared while the others are being played, the first

and fourth fingers being always ready to press down the black rows without shifting

the other fingers (Complete Instructions, p. 6). 9

Warren, then, breaks with what I’ve called the “mainstream” fingering in which the first finger covers vertical rows 1 and 2, finger 2 covers row 3, and the third finger covers row 4 (see Blagrove’s prescription above). Here, finger 1 does not do double duty, as it covers the “black notes” of row 1 only.

We see Warren’s idea in action upon turning to the appendix, where we find his “New System of Fingering.” Example 6 shows his fingering for the scales of A major and E-flat major, as well as that for a one-octave ascent through a chromatic scale.

Ex. 6. Warren, Complete Instructions, p. 69: (a) A-major scale (Warren’s indication

of finger 4 on the high f’’’ sharp is obviously a typographical error, and I have

emended it with [1]; (b) E-flat major scale (both scales complete); (c) chromatic

scale (one octave only); in place of Warren’s quarter notes without barlines, I give

note heads only.

For whom, though, is this “New System” intended? Did Warren think that the Blagroves, Cases, and Regondis of the concertina world would alter their technique and adopt the “New System” in their own playing? Or was he addressing the beginner, who, perhaps he (Warren) hoped, was coming to the instrument with no preconceived notions? Is the system in fact “new,” or are we dealing with an already-existent “unwritten” tradition? I have no answers!

Among the Victorian-era method books that I consulted for this project, only one other adopts Warren’s “New System”: The Modern English Concertina Method (London: Lachenal, c. 1895) by the self-styled “Signor Alsepti,” who prescribes it (if inconsistently) with a vengeance. 10 He writes (all italics are Alsepti’s):

As the fourth finger of each hand is to be used as frequently as the other fingers,

the pupil should never use the metal plates . . . as a rest for that finger. These

rests are only useful as a guide. . . . The first finger of each hand must cover the

first (or top) row of keys, the second fingers must be held over the second row.

The third fingers cover the third row, and the fourth fingers cover the fourth (or

or lowest) row of keys . . . (Method, p. 7).

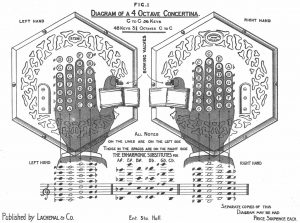

And to avoid any possible confusion, Alsepti offers an illustration of the button boards that shows each finger relegated to its own row (see Fig 2). 11

Fig. 2. Alsepti, Method, Fig. 2.

Example 7 shows how the method works in practical terms.

Ex. 7. Alsepti, Method, p. 18: “Melody in A Major,” meas. 1-4, 12-16.

Yet in transmitting what he calls “Regondi’s Golden Exercise” (Ex. 8), Alsepti, who claims that he studied with Regondi, often contradicts his own one-finger/one-row prescription, and the fingering sometimes seems to be neither here nor there. In the end — and since the “Exercise” appears nowhere else — we can only wonder if Alsepti’s fingering is a conflation of sorts. 12

Ex. 8. Alsepti, Method, p. 38: “Regondi’s Golden Exercise,” meas. 1-4;

asterisks identify the fingerings that conflict with Alsepti’s one-finger/

one-row method.

Perhaps the “wrong” fingers stem from Alsepti’s resolve not to use the same finger even on almost-successive notes in a given hand, that is, even when there is an intervening note between them.

In the end, to judge from contemporary method books, neither Warren’s “New System” nor Alsepti’s adoption of it seems to have had much influence.

(3) Skepticism about using the fourth finger: The author of no fewer than seven method books (see note 6), George Case was skeptical about the use of the fourth finger. He says as much on two occasions in his Instructions for Performing on the Concertina: “ . . . the rests or plates in a line with [the thumb] straps are for the fourth fingers,” which statement is then left unqualified (Instructions, p. 4). And later, in what constitutes an Appendix:

It will be remarked that in the following Grand Exercise, the fourth finger is

introduced. This is sometimes necessary in very elaborate compositions,

although the Author is not a great advocate for its general use [my emphasis]

(Instructions, p. 58).

There follows the “Grand Exercise” (Ex. 9):

Ex. 9. Case, Instructions, p. 60, meas. 41, 45-46.

With the third finger sustaining the b’ flat, there would be no other way to negotiate the e’ flat and low a flat in measure 41. In measure 45, the stretch from a flat to the high e’’’ flat would be difficult (if not somewhat painful) using fingers 3 – 1, with the problem even further exacerbated by having to use finger 2 on the a’’ flat (in 1849, an enharmonic g’’ sharp was not yet possible).

Indeed, Case seems to have been skeptical enough about the use of finger 4 to go out of his way on occasion to avoid it. In its place he will switch fingers while sustaining a note (Ex. 10a), slightly contort finger 2 to get it on the c’’’ sharp (Ex. 10b), and use the same finger on two notes (simultaneously) that are obliquely adjacent to one another (Ex. 10c). 13

Ex. 10. Case, Instructions: (a) changing fingers on a sustained note, “In Three

Parts,” Exercise 68, meas. 11 (p. 48); (b) finger 2 slightly contorted, “On Full

Chords,” Exercise 69, meas. 5 (p. 49); (c) one finger simultaneously on obliquely

adjacent notes, “On Full Chords,” Exercise 69, meas. 44-45 (p. 49).

If Case leaves us with an unanswered question, perhaps it is this: just what does he mean when he says that he is not “a great advocate of [finger 4’s] general use” (my emphasis)? Is he, as I think he is, taking issue with, say, the views of Regondi and Blagrove, who use finger 4 whenever they deem it necessary, or is he possibly railing against the dogmatic use of the fourth finger in Warren’s “New System” (which, however, does not seem to have been in “general use”)? Once again, I have no answers.

(4) No fourth finger: Finally, there were at least some Victorians who saw no need for the fourth finger at all. Thus Robert Cocks & Co.’s Handbook and Carlo Minasi’s Concise Method relegate finger 4 to its finger rest (and leave it there), while W.F. Prussak’s German-language Schule fails to mention that finger at all. 14

To sum up: although the use of the fourth finger was an essential tool in the Victorians’ technique (and absolutely necessary for anyone who would tackle the virtuoso-level compositions by the likes of Regondi and Blagrove), the leading concertinists of the period were by no means of one mind about just how to use it. As we have noted, practices ranged from (1) the liberal but non-“rule”-bound use of that finger by Regondi, Blagrove, and Sedgwick (though we have seen that they did not necessarily agree among themselves even on so basic a matter as fingering an E-major scale in sixths) to (2) the “one-finger/one-row” dogma of Warren (at least as outlined in his “New System”) and Alsepti to (3) the skepticism of Case to (4) the “never-use-finger-4” prescriptions of Cocks, Minasi, and Prussak. Moreover, there was — already early on — something of a consensus that the use of the fourth finger was to be reserved for advanced players (and even, according to Warren, for “professors”) only.

Finally, I would end with two important caveats:

(1) Although we have distinguished between what our method books say, we have not considered why they say it; or, to frame the matter another way (one suggested to me by Wim Wakker): to what extent were the different views about the use of finger 4 generated at least in part by different goals and purposes? To explore this, however, goes beyond what I have set as my own goals for this relatively brief and basically expository note. 15

(2) My report is based on a study of ten method books that date from 1844 to almost the end of the century. Yet for that same period, Merris lists no fewer than fifty-three such publications. 16 Would the forty-three method books that I did not consult have altered the picture that I have drawn? Though I would like to think (I cannot say that I know) that they would not, I must, for the third time now, admit that I have no answers!

- Anderson, Concertina Workshop: Tutor for the English Concertina (London: Topic, 1974); Butler, The Concertina: A Handbook and Tutor for Beginners on the English Concertina (Duffield: Free Reed Press, 1974; reissued New York: Oak Publications, 1976 – online at “Concertina Library, Digital Reference Collection for Concertinas,” http://www.concertina.com/butler/butler-the-concertina-tutor.pdf); De Snoo, Concertina Course, Volume One (Schijndel [NL]: De Snoo, 2002); Atlas, Contemplating the Concertina: An Historically-Informed Tutor for the English Concertina (Amherst, MA: The Button Box, 2003); Wakker, Tutor for the Jackie and Jack English Concertinas (Valleyford, WA: Concertina Connection, 2010); for a list of other English-system tutors from this period, see Randall C. Merris, “Instruction Manuals for the English, Anglo, and Duet Concertina: An Annotated Bibliography,” The Free-Reed Journal, 4 (2002), 89-99, 118; online (and updated) at “Concertina Library,” http://www.concertina.com/merris/bibliography/.

- Alfred Edwards, Wheatstone’s Instructions for the English Concertina (London: Wheatstone, 1960), 9.

- Regondi, Rudimenti del Concertinista, Or a Complete Series of Elementary and Progressive Exercises for the Concertina (London: Joseph Scates, 1844); New Method for the Concertina (Dublin: Joseph Scates/London: Wessel, 1857); Blagrove, Instruction Book for the Study of the Concertina, Comprising Elementary and Progressive Exercises (London: Cramer, Wood, 1864); online and with my introductory essay in “Brief Notes,” No. 4, this JOURNAL (posted 17 December 2017); Sedgwick, Complete System of Instructions for the Concertina (London: Levesque, Edmeades, 1854); Warren, Complete Instructions for the Concertina, 4th ed. (London: Wheatstone, c. 1855, to which edition subsequent citations refer); the 2nd edition (1852), which is very similar to the 4th, is available online at https://play.google.com/store/books/details/Joseph_Warren_Complete_Instructions_for_the%20Concertina?id=qgrWoc1q0YwC. To the extent that present-day concertinists are familiar with Warren’s method book, it is probably through the 9th edition, which was reprinted and issued by Jenny Cox (Bristol) in 1998; that the title page of the 9th edition gives Wheatstone’s address as 15 West Street, Charing Cross Road, indicates that it was issued in 1905 or later.

- I consider “not as yet” to refer to 1852 on the grounds that the 4th edition (c. 1855, from which the citation is taken) lifts the passage directly from the 2nd edition (1852).

- I discuss this at some length in both Contemplating the Concertina, 15, and “‘2/1’ v. ‘1/2’: Victorian Fingering on the English Concertina,” Concertina World: Magazine of the International Concertina Association, 465 (March 2016), 32-40.

- Case, Instructions for Performing on the Concertina (London: Wheatstone, 1849), 12 (Case’s emphasis); Boosey & Son issued subsequent editions c. 1854 and c. 1875. Case turned out six other method books for the instrument (including what seems to be the only one for the baritone concertina); see Merris, “Instruction Manuals,” 91-92. With its selection of psalm settings arranged for the concertina, the baritone tutor, published as The Baritone Concertina, a New Method (London: Boosey, 1857), reminds us of that instrument’s role in small parish churches that did not have an organ; see Atlas, The Wheatstone English Concertina in Victorian England (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), 6-7.

- Whereas Regondi offers an exercise on a chromatic scale in single notes in the Rudimenti (p. 18), he limits his chromatic-scale “workouts” in the New Method to dyads only: 3rds, 6ths, octaves, 10ths, and a particularly devilish one in contrary motion (pp. 17-18). Neither Blagrove (Instruction Book) nor Case (Instructions) asks the student to wrestle with the chromatic scales in anything other than single notes.

- On the tunings and the conversion from meantone to equal temperament (which, to judge from some of the music being written for the instrument must have at least begun to occur in the late 1850s/early 1860s), see the summary in Atlas, The Wheatstone English Concertina, 39-47; and “The Victorian Concertina: Some Issues Relating to Performance,” Nineteenth-Century Music Review, 3/2 (2006), 46-54 – online at “Concertina Library,” http://www.concertina.com/atlas/victorian-concertina-performance/. Obviously, the shift from one temperament to the other did not take place over night; and in 1865 William Cawdell wrote that concertinas were available in both tunings (Cawdell, A Short Account of the English Concertina: Its Uses and Capabilities, Facility of Acquirement, and Other Advantages [London: William Cawdell, 1865], 6 – online at “Concertina Library,” http://www.concertina.com/cawdell/), while as late as 1891, the concertinist John Charles Ward could state that “amongst inferior makers the unequal temperament and other defects still flourish . . .”; Ward, “The English Concertina” (Letter to the Editor), Musical News, 21 August 1891, p. 511 (cited in Atlas, The Wheatstone English Concertina, 47).

- Although the phrase “some exercises have been added” implies that what Warren is describing is new to the 4th edition, the exercises had already appeared in the 2nd edition (p. 65), from which the 4th edition lifted the above passage without alteration (see note 4). I have deleted an errant semicolon after “the first and fourth fingers being only used . . .”

- As I have shown elsewhere, “Signor Alsepti” is the Exeter-born James Alsept (1837-1897); see my article, “Signor Alsepti and ‘Regondi’s Golden Exercise’,” Concertina World: Newsletter of the International Concertina Association, 426/supplement (2003), 1-8; online at “Concertina Library,” http://www.concertina.com/atlas/regondi-golden-exercise/index.htm.

- Note that Lachenal offered the diagram as a separate publication for the price of sixpence.

- Alsepti, Method, 38, writes about the “Golden Exercise”: “The following exercise, which has never before been published, was taught to Signor Alsepti by Regondi. It is very difficult for all instruments, especially the Concertina, and to throughly [sic] master it with the correct fingering &c will enable the Pupil to play passages in all keys.” I offer a revised, three-finger fingering as Example 2 in “Signor Alsepti and ‘Regondi’s Golden Exercise’.”

- Prescriptions for the use of one finger simultaneously on two notes occur most often in connection with notes that are one above the other in the same vertical row, one above the other (see Ex. 3d).

- Robert Cocks & Co.’s Hand Book of Instructions for the English Concertina, with 32, 40, and 48 Keys (London: Robert Cocks, 1855), 4; Minasi, A Concise Method for the Study of the Concertina, rev. ed. (London: Ashdown, c. 1880), 6 (originally published by Boosey, c. 1853); on Minasi, who was a rather fascinating fellow, see Merris, “Carlo Minasi: Composer, Arranger, and Teacher, Concertina and Piano,” Papers of the International Concertina Association, 6 [2009], 17-45; Prussak, Neue vervollkommnete, leichtverständliche, praktischer Schule für die englischen Concertina (Berlin/Leipzig: Zimmermann, c. 1890), 2; reissued as Schule für englischen Concertina. Zimmermann-Schule, No. 37 (Frankfurt: Zimmermann, 1982).

- I would hope that Wim himself will address the question in this JOURNAL in the near future.

- Merris, “Instruction Manuals,” 89-99.