An Ergonomic View

Göran Rahm

Introduction

The role of the fourth finger on the English concertina is problematic owing to its double-duty workload: (1) it can help to hold the instrument, 1 and (2) it can be called into action on the button board. 2 Yet we may question the ability of the fourth finger to execute either of these tasks effectively, while any attempt to perform both of them simultaneously results in insurmountable obstacles. The object of this brief note is to illustrate these problems from an ergonomic point of view that focuses on the anatomy of the hand, something that has not received proper attention until now.

Two issues

(a) The holding role: The role of the fourth finger as a means of holding the instrument has changed since Charles Wheatstone described the concertina in his patent of 1844: “The instrument is held by placing the thumb in the loop . . . and the third and fourth fingers [my emphasis] against the finger plate. . .” 3 It was during the course of the nineteenth century that the fourth finger took on its dual role. In his Rudimenti del Concertinista (1844), Giulio Regondi writes: “The fourth finger of each hand must (except when employed in playing) rest against the projecting plate opposite the loops.” 4 By the time he wrote his New Method for the Concertina in 1857, however, he had changed his view: “… the fourth finger plates … are useful to beginners in order to balance the hands … but in a more advanced stage … it is useless or even bad to accustom the fourth finger to press tightly on the holders.” 5 Finally, the twentieth century has relegated the fourth finger mainly to a holding role. Echoing the prevalent view, Frank Butler puts it as follows in The Concertina (1974): “The little fingers should rest under the finger plates, so that the weight of the instrument is taken on the thumbs and little fingers.” 6

The crucial question, however, is whether or not the fourth finger is anatomically fit for this service at all. There is a physiological general rule: a muscle is capable of untroubled, prolonged static effort when it carries a load that is less than about ten percent of its maximal power. Yet to grip a treble concertina that weighs, say, 1,500 grams (approximately 3.3 pounds) while also manipulating the bellows at the same level of effort demands greater exertion than we might expect from the average individual. Although resting the instrument on the knee or using some kind of suspension (a neck/shoulder strap, for instance) may reduce the amount of effort needed, the poor stability of the instrument/player connection means that the fourth finger generally cannot be expected to perform the required amount of holding/stabilizing work.

(b) The fingering role: As noted above, the role of the fourth finger has been subject to various opinions and recommendations, from being as active on the button board as the other fingers to not being used at all. Surprisingly from an ergonomic point of view, discussions of the matter have, among other things, entirely disregarded such factors as the anatomical variations of the length, width, and agility of hands and fingers, conditions that ultimately determine what methods and solutions are actually feasible for the individual player.

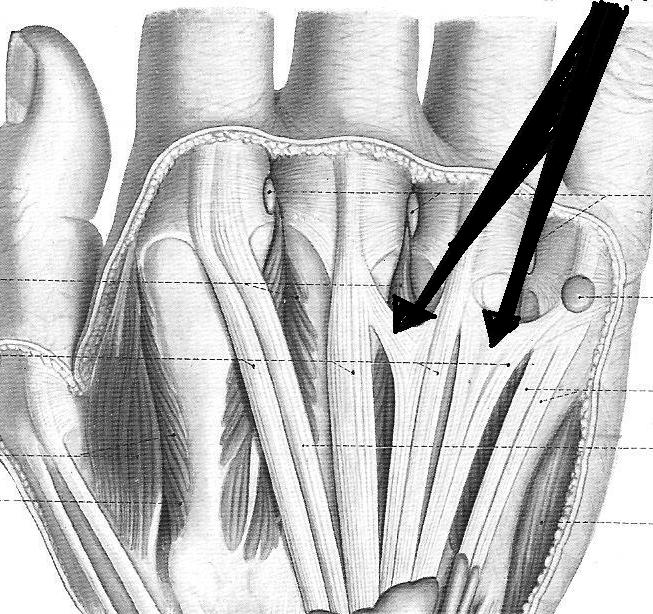

For example, the length of the fourth finger varies from almost the length of the third finger to only about half as much, something that will obviously have an effect on the capacity of that finger to play and hold. There is, however, an anatomical factor of even greater importance, one that has not received widespread attention (though I have occasionally mentioned it on the Concertina.net forums): the extensor tendons of the second, third, and fourth fingers are linked together by connective strings, so that those fingers cannot move entirely independently of one another (Fig. 1)

Thus if the fourth finger is kept tucked into the finger plate, the mobility of the third finger in particular, but also that of the second is impaired. Nor does one have to grip tightly with the fourth finger; just touching the finger plate is enough to cause the impairment.

The practical significance of these circumstances may be demonstrated by a simple experiment.

Case 1: Rest the thumb against a table with the other four fingers in the air (Fig. 2a), and then perform a trill as fast and as steadily as possible by alternately tapping first with fingers 1 and 2, then with fingers 1 and 3, and finally, with fingers 2 and 3.

Case 2: Now repeat these steps while also resting the little finger gently against the table (Fig. 2b).

Case 3: Finally, repeat the three steps once again, now while gripping the box of a compact tape cassette (or something similar) and holding it in the air with the thumb and the fourth finger (Fig. 2c).

Case 2 illustrates the influence of the connecting strings between fingers 2, 3, and 4, while Case 3 shows that of static effort in combination with dynamic work. In practical terms, the trill slows down and becomes ever more uneven as we go from one case to the next, especially in connection with the trill that involves fingers 2 and 3.

Conclusions

Owing to the instability of the English concertina’s “handle” (that is, the combination of thumb strap and finger plate), the fourth finger (even in combination with the thumb) lacks sufficient holding capability. Moreover, keeping the fourth finger in the finger plate inhibits the movement of the other fingers.

In all, the design of the English concertina itself results in inevitable conflicts between the need for stability (static effort while holding the instrument) and the flexibility (dynamic work while fingering the button board). The fourth finger should not be involved in any kind of holding activity. Whether or not it participates on the button board is a secondary matter; for even if not using the fourth finger on the buttons, it is preferable to keep it in the air, silently trailing the other fingers. As a consequence of this, a reconsideration of some traditional recommendations and playing methods is clearly called for.

- Note that I distinguish between “holding” and “supporting.” I use “holding” (or “hold”) to refer to the contact that involves thumb (in its strap) and fourth finger (in the finger plate); thus one can “hold” the instrument even if it’s resting on a table. On the other hand, “supporting” (or “support”) refers to the likes of a neck/shoulder strap or resting the instrument on one’s knee or lap in order to offset its weight.

- I use standard concertina fingering: 1 = index finger, 2 = middle, 3 = ring, and 4 = little finger.

- Wheatstone, “Improvements in the Action of the Concertina, etc. by Vibrating Springs,” British Patent No. 10041 (7 August 1844), 3; online at “Concertina Library,” http://www.concertina.com/wheatstone/Wheatstone-Concertina-Patent-No-10041-of-1844.pdf.

- Regondi, Rudimenti del Concertinista, A Complete Series of Elementary & Progressive Exercises for the Concertina (London: Joseph Scates, 1844), 1.

- Regondi, New Method for the Concertina Dublin: Joseph Scates/London: Wessel, 1857), 2. For a survey of nineteenth-century attitudes toward the use of the fourth finger, see Allan Atlas, “The English Concertina and Finger 4: Four Victorian Views,” The Concertina Journal, “articles,” no. 3 (April 2018); online at https://www.concertinajournal.org/articles/the-english-concertina-and-finger-4.

- Butler, The Concertina: A Handbook and Tutor for Beginners on the English Concertina (Duffield [UK]: The Free-Reed Press, 1974), 7; online at “Concertina Library,” http://www.concertina.com/butler/butler-the-concertina-tutor.pdf.