The Concertina in Australia

Warren Fahey

Editor’s Note: The concertina has had a long history in Australia, and is still actively played all over the country. Warren Fahey, our Journal’s Correspondent from Australia, has kindly attempted to put this history into perspective, as well as provide a description of where it can be heard today.

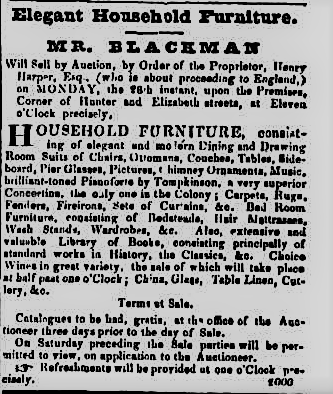

The English concertina’s first documented appearance in Australia was 1841, a mere fifty-three years after the arrival of the First Fleet of convicts and marines, and a year before Sydney was declared Australia’s first city. The instrument appears to have belonged to a land agent and general auctioneer, Mr Blackman, who had rooms for some years at The Terrace, Hunter Street, Sydney. In that year, Mr Blackman, ‘who is proceeding back to England’ advertised his personal belongings in the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, including ‘a very superior concertina – the only one in the colony’. Considering that Mr Blackman had been a Sydney resident for some years, we can only speculate whether he had brought the concertina from England or had ordered it to be shipped. Maybe some diligent researcher can trace Blackman’s name back to the Wheatstone sale ledgers.

The ‘colonials’ had already read about the instrument in an 1837 newspaper article (The Sydney Herald, 23 Nov. 1837) reporting on the Covent Garden Theatrical Fund Dinner, in the Freemason’s Hall, where ‘Giulio Regondi performed very brilliantly upon Wheatstone’s Patent Concertina’. Though ‘The Great Regondi’ is probably better remembered as a guitar virtuoso and composer, he was also one of the first virtuosos of the concertina, as this report from The Times, 26 April 1837 attests:

GREAT CONCERT-ROOM – KING’S THEATRE. There was also a novelty in the shape of an instrument called ‘a concertina,’ an improvement on the accordion, which has been such a favourite musical toy for the last two or three years. The tones of this instrument are sweet and pleasing; but far more striking than the concertina itself were the feeling and ease with which it was played by that clever little boy Giulio Regondi, who executed several intricate passages with surprising facility and precision.

One can only speculate as to how many concertinas arrived in Australia between 1840 and 1850. However, considering the number of emigrants, public officials and their families, as well as the general interest in the new instrument at that time, it is highly likely that concertinas were included in the luggage of many travellers. The voyage from Southampton to Melbourne could take four or five months, and musical evenings were considered an important part of shipboard well-being. The concertina, being small and portable, was popular on these journeys. There was also the fact that parlour music and semi-classical music, both well-suited to the instrument, were seen as a ‘civilising’ opportunity for emigrants. There must have been plenty of time to practise on the high seas.

It is interesting, as an aside, to note that our ‘convict birth’ and subsequent rural upbringing in the 19th century both influenced our folk music. There were more English convicts transported here than Irish, Welsh or Scottish. There is little doubt that Australian bush music sounds distinctive – it has a unique sound that salutes our pioneering heritage. Instrumentation was primarily free-reed and string instruments, keyboards and percussion.

ADELAIDE – THE CITY OF CHURCHES (AND CONCERTINAS)

It is not surprising to find that Adelaide, the capital of South Australia and the only colony not to have convicts, had more newspaper reports about concertinas than did any other colony. ‘Unblemished’ South Australia was seen as a safe place, especially for female emigrants, and was considered both religious and artistic.

On 6 March 1850 the Adelaide Times reported:

A gentleman, recently arrived from England, has, in his possession, a most beautiful Concertina, on which he plays exquisitely. We had the pleasure last evening at the Clarendon Hotel, of hearing him play two or three marches and airs upon it from different operas in first-rate style. This instrument must not be confounded with the Accordion, or Flautina, the tones are far richer and most powerful; almost sufficiently so for some of the small places of worship here. It would be a very great addition to any future concert that might be given.

On 29 March the Adelaide Times advertised “Six grand promenade concerts” that featured an amateur player “solo on concertina,” declaring it the “first time in this colony.” The South Australian reviewed the concert on 5 April:

Among the most successful pieces, we may mention the solo on the Concertina, a novel and beautiful instrument, and that on the Tuber Basso, which was enthusiastically encored. The trumpet polka and the drum polka were also much admired. On the whole, we have never seen a concert in the colony go off better or give more general satisfaction.

THE DISCOVERY OF GOLD LED TO MORE CONCERTINAS

The discovery of gold in New South Wales and Victoria in 1851 turned considerable international attention on Australia. Would-be fossickers travelled to the ports of Sydney and Melbourne, then scrambled to the inland goldfields. They took with them what they could carry, typically a shovel, a rucksack of provisions and a few personal mementoes. It is unlikely that many musical instruments were included in the packs of the first wave of diggers. Fiddles and concertinas probably came in the second wave, as stagecoaches travelled back and forth to the goldfield tent cities. These were crazed times, and Australia’s population increased by well over a million persons in just twenty years. The gold rush had dramatically increased the number of ships on the Australian run, and freight became an important business for shipping lines.

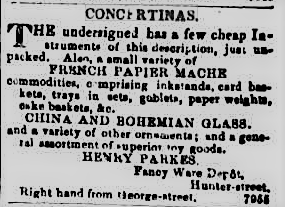

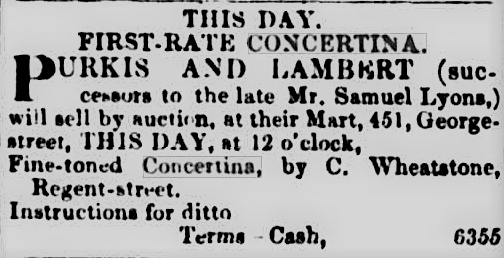

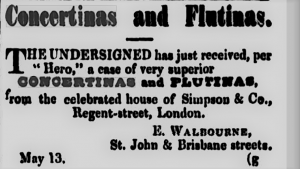

Tent cities quickly became towns, and the ‘singing halls’ an important part of goldfields entertainment. Quantities of concertinas started to appear in all the colonies as merchants imported shipments from England. Many auctions for these instruments were conducted on the wharves immediately after the ships had landed. Advertisements for concertinas started to appear in all colonial newspapers. Many described the wood – rosewood, blackwood, walnut, etc.

The Courier Hobart of 22 February 1851 advertised, ‘Concertinas of the latest patent improvement, with books of instructions that either lady or gentleman may teach themselves this splendid accomplishment; so much the rage in all respectable families.’ The Sydney Morning Herald of 31 March 1851 announced the sale of a ‘ROSEWOOD SERAPHINE CONCERTINA, Wheatstone’s patent double action, with instructions, case – the only one for sale in the colony.’

THE CONCERTINA CANNOT BE SOUNDED OUT OF TUNE

It appears that the concertina gained a solid market in Australia fairly quickly, and Sydney’s main music retailer, W. J. Johnson, advertising in the Sydney Morning Herald of 10 Jan 1852, opens with:

The Concertina is now so well known, that it is hardly necessary to say it possesses qualities which have never hitherto been combined in a single musical instrument; it is equally adapted to the most expressive performance, and the most rapid execution whether confined to the succession of single notes, as most other wind instruments are, or in harmony of two, three, or four parts. It is very easy to learn on account of the remarkable simplicity of fingering, and the great facility with which its tones are produced and sustained; and as it cannot be sounded out of tune, the most perfect crescendos and diminuendos may be obtained without the practice requisite on other instruments – to these advantages may be added the peculiar beauty of its tones and its extreme portability. The Concertina is capable of performing music written for the flute, violin, or any other instrument; besides which, much music has been written expressly for this instrument.

The undersigned has now on view a few of the above beautiful instruments and instruction books.

W. J. JOHNSON.

THE CONCERTINA GOES BUSH

Later that year a Sydney retailer made the first connection between the concertina and the ‘bush’. In those days the ‘bush’ referred to anywhere out of the capital cities or main coastal town centres, even if not necessarily a long distance. The term ‘bush’ was used as early as the 1810s, as ‘forest’ or ‘wood’ didn’t seem at all applicable to the impenetrable and seemingly hostile bush. As we now know, the concertina found a ready home in the bush and was a favourite of the itinerant workers.

One story from Smith’s Weekly of 26 September 1931 recalled a character called ‘Concertina Dick’:

An old-timer on the Darling was known as Concertina Dick. He was a shearers’ cook, who could inflate himself like a scared frog. Sometimes he took his shirt off in camp, and entertained the company with wonderful rib contortions. Like many of the old identities of the river, known for hundreds of miles through the back country, he did the rounds of the sheds at shearing time, and retired to his fishing ground in slack periods. But wherever he was, he always had a concertina, which he played day and night. He was cooking one year in a Paroo shed, where the constant screamer wasn’t appreciated as unanimously as Dick expected, and one evening, when he picked it up to ‘give ’em a tune,’ he could get nothing out of the instrument, but dull, weird squeaks – and a bad smell. On screwing the top off, he found the interior half-full of wet cow-dung. “Some dirty cow think’s he’s funny,” Dick snorted, and thenceforth there was peace.

The popularity of the concertina, particularly the Anglo and Duet, was closely associated with dance music. The popularity of dances like the polka and schottische encouraged many players, and sheet music was both imported and printed locally. It wasn’t unusual for a nineteenth-century bush dance, often staged in a woodshed or local church hall, to have music supplied by the one local who played an instrument; often it was a concertina. The player would also have to cope with playing half the night because these social gatherings were rare and the dancers often refused to leave. The player had to pace himself, and develop playing styles that didn’t wear him or her down during the long dances.

LEARN THE CONCERTINA IN HALF AN HOUR!

From the Sydney Morning Herald of 28 Aug 1852:

CONCERTINAS, with instruction books. These instruments are peculiarly well adapted for the bush. The concertina is the easiest, most beautiful, and portable of all musical instruments yet invented and stands well in the most tropical climates. The fingering is so extremely simple and the tones so easily produced, that any person may, in the course of half an hour, be able to play a simple tune. W. J. Johnson.

ENTER THE PROFESSORS

With the increased popularity and availability of concertinas came professional recital artists and teachers. Many of these expert players assumed the title of ‘professor’. Henry Richardson was one of the earliest. The Sydney Morning Herald of 1 Jan 1853 announced:

Mr HENRY RICHARDSON, Professor of the Concertina, (Pupil of Signor Giulio Regondi and Mr George Case) who has recently arrived from London, is desirous of giving publicity to his intention immediately to commence the practice of his profession. A portion of the community are necessarily unacquainted with the merits and capacity of this delightful instrument; though facility of execution, purity of intonation, harmonic effect, and variety of expression, in every style of composition, sacred and secular, of which it is capable, have secured for it an unqualified supremacy in the higher circles in the United Kingdom, where it is now practised, by both ladies and gentlemen, to a wonderful extent, its recent invention considered.

The Sydney Morning Herald of 20 Jan 1853 reviewed one of Mr. Richardson’s performances on the English concertina:

A crowded and fashionable audience gave Mr Richardson a cordial welcome on Tuesday evening, in the theatre of the School of Arts, upon the occasion of his presenting illustrations of the capabilities of the Messrs. Wheatstone’s far-famed instrument, the Concertina. Various weak imitations of this instrument – the Accordéon and the Flautina, for example – have been introduced here of late years, but they are mere toys when compared with what may justly be termed a result of the “mathematics of music.” About seventeen years ago, the attention of musical performers was directed to the question, whether the duplicity of the dissonances is not the solution of the difficulties that attach to the correct division and execution of the musical scale. In this discussion, the Messrs. Wheatstone took a prominent part, and amongst the practical results of the investigation of this theory, was the introduction of the concertina – a most welcome contribution to musical science. Constructed with a view to the execution of every kind of music, however elaborate, however simple, it at once found favour with both amateurs and professional musicians, and we are not surprised that it was not long in exhibiting the capabilities of this instrument. Mr Richardson displayed not only masterly execution but the best taste. His repertoire included the opening of La Sonnambula, wherein Lisa mourns her ruined hopes. The second was a popular Tyrolean air, with variations by Sedgwick. The third was a delightful arrangement by George Case, of an Austrian air; and the fourth was Donizetti’s matchless serenade,“On Summer Night,” from Don Pasquale. Rapturous encores testified the delight and surprise of the audience and their appreciation of the taste which had selected these beautiful compositions. Mr Richardson also played an obligato accompaniment to Mr Waller’s song of “Hear me, gentle Maritana.” We ought to have observed that the concertina commands the complete chromatic scale and that full harmonised passages are perfectly rendered. Mr Richardson was assisted by Mrs St. John Adcock, Mr Waller, and Mr Sigmont, and the concertina soiree must be cited as another hit for the School of Arts.

A year later, in 1854, George Case, the noted musician and concertina builder, visited Australia for the first of several tours.

OH, SUSANNAH!

One of the favourite entertainments of the mid-nineteenth century was the minstrel show. Several American and British troupes toured Australia and the music held its popularity until around 1910. Many country towns formed their own minstrel troupes, and the concertina was a popular instrument in many of them. The minstrel repertoire consisted mostly of the popular Oh, Susannah style of song – typically from Stephen Foster – and such songs achieved extremely wide circulation. Many of these songs were also used as parody songs and became the basis for what we refer to as ‘bush songs’.

The Anglo-German concertina made a large impact on Australia, especially with its repertoire of folk music. Large shipments of Anglo concertinas arrived in the later part of the gold rush era, and the instrument soon jumped into the bush to become the favourite of bush dance accompanists. The number of Anglo-German concertinas soon outnumbered the English concertina, which, one suspects, was still thought of primarily as an art music instrument.

Here are two recordings I made of Mrs Susan Colley in 1973. Mrs Colley, an Anglo player was 92 years old when I recorded her version of the Varsoviena (She called it the Arse-Over-Anna). Mrs Colley plays a Stanley Concertina (see below):

Susan Colley’s Varsoviena

Susan Colley speaks about playing for bush dances, plus the tune Ebb Wren

The second cut here features Mrs Colley talking about old-time bush dances and her playing the concertina behind her partner’s back as they danced the polka. The tune that follows, Ebb Wren, was collected by Rob Willis and is played by my band, The Australian Bush Orchestra. The album of that title contains various cuts from my field recordings married to new arrangements.

THE BUSHMAN’S INSTRUMENT

As a bush instrument, the concertina travelled Australia in portmanteau bags, saddle bags and even swags. It is mentioned in many bush stories and celebrated in poetry and song. It became synonymous with the campfire and the so-called woolshed dance.

It is important to note that all models of concertina were played in Australia. However, using the instrument to accompany one’s own singing appears to have been a rarity. In truth, the Australian bush song tradition (some refer to this as Australian folk song) is primarily unaccompanied. This is not to say that bushmen didn’t sing with the concertina, but there are scarce mentions of it, and one is hard-pressed to cite a field recording where both are combined. This, of course, has not stopped modern-day interpreters from accompanying themselves.

Just like ‘forest’ and ‘wood’ seemed inappropriate terms for the ‘bush’, so too was ornamentation generally considered inappropriate. Australia, especially the outback, is harsh and remote. This remoteness affected our language, laconic sense of humour and, possibly, the role of ornamentation in traditional music. The music reflects the environment.

Gooriannawa is a typical shearing song. It mentions some of the great shearing stations. I sing it accompanied on my Lachenal Edeophone.

Gooriannawa, played and sung by Warren Fahey.

SQUEEZING INTO THE SLANGUAGE

The concertina also went into the Australian ‘language’. Shearers often referred to a sheep as a concertina because of the wrinkles in its skin. Concertina leggings were developed to protect the ankles of bush workers from the thick undergrowth and thorny prickles. Bush cooks referred to a side of mutton as a concertina of mutton because of the ribs. Concertina wire is a type of barbed or razor wire that is formed in large coils which can be expanded like a concertina. Australian soldiers in WW1 made their own concertina wire using standard barbed wire.

THE CONCERTINA GOES TO TOWN

Concertina playing continued steadily from the heady gold rush days, through the rural boom years of wheat, wool and beef, into the early twentieth century. At that latter time the population shifted away from working and living primarily in the country to living in coastal cities, where people worked in factories and in commerce. The concertina travelled too, and was found on the vaudeville stage, in Salvation Army bands and in the hands of its most fanatical players, the street larrikins. The larrikins were a city phenomenon, and an ugly one to boot. They were street roughs who acted in gangs, creating mischief. They first appeared in the 1870s and remained a nuisance until around the late 1920s. The concertina was their favourite instrument and their greatest delight – apart from fighting and being a threat to public civility – was dancing. They were known to take over public spaces, crank up the concertina, and polka and waltz far into the evening.

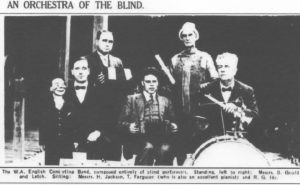

The instrument, being heavenly, also found itself in the hands of various evangelical preachers. One even described himself as ‘The Concertina Bloke’. The Salvation Army, particularly strong in the Australian bush, typically had three or four concertina players per band. I have recorded two Salvation Army players and, sadly, their repertoires were restricted to hymns.

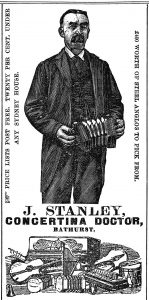

JOHN STANLEY, THE CONCERTINA DOCTOR OF AUSTRALIA

Australia had one maker of concertinas. John Stanley operated from a shop in the main street of the west New South Wales regional town of Bathurst. He repaired, adapted and made Anglo-German concertinas between 1880 and 1900. He advertised that his Stanley Concertinas were particularly loud and well-suited for dance accompaniment. It has been rare to find a Stanley, however, I was fortunate to find one this year (I only know of two others). Both Stanley’s and the purchaser’s names were engraved very predominately into the fretboard.

There is an essay on John Stanley at http://www.warrenfahey.com.au/concertina-doctor-of-bathurst/

THE CONCERTINA IN HARD TIMES AND LEAN TIMES

The concertina went to the Boer War and to the First World War. Along with a few other portable instruments like the mouth organ, whistle, and banjo mandolin, it was much favoured by the troops for singalongs.

By the 1930s the concertina seemed to have disappeared from favour. It no doubt came out for a few Depression-year singalongs, but radio was becoming a dominant force and recorded music sales were soaring. Like much of the western world, we were becoming a nation of people who got entertained, rather than entertaining each other. Dances in the country still retained their typical bands of violin, piano, button accordion and concertina. City dance bands were mainly large jazz ensembles, heavy on brass and keyboard instruments.

THE CONCERTINA IN POPULAR CULTURE

The concertina popped up in some of the strangest places, cartoons, comic strips and advertisements being just a few. Children’s pages even had a ‘How to Make Your Own Concertina’ guide!

The concertina also appeared in WW2 political cartoons.

THE FOLK REVIVAL (WHATEVER THAT IS)

After a brief resurgence during World War II, the popularity of the concertina was on a steep decline. It wasn’t until the international folk music boom of the 1950s that the concertina began to reappear, albeit quietly. By the 1960s, a few British migrants and travellers, notably Mike Ball, Colin Dryden and Carol Wilkinson, all English concertina players, performed at folk festivals and clubs. A resurgence of interest in Australian bush songs and dancing in the late 1960s and early 1970s also saw a revival of interest in the concertina, and many ‘bush bands’, revivalist interpreters of bush songs, incorporated a concertina, typically an Anglo-German. You can read about various aspects of the Australian folk revival, including concertina players, at http://www.warrenfahey.com.au/enter-the-collection/australian-folk-revival/

THE CONCERTINA TODAY, AND RESOURCES FOR THE CURIOUS

The Australian folk scene of today covers many musical genres, and the concertina is likely to appear in anything from world fusion to Celtic music, and from bush music to the accompaniment of the British ballad repertoire. The main focus of folk music in Australia today appears to be the solid network of festivals. Some, like the National Folk Festival and the Woodford Festival, are big events, and others, like Cobargo and Kangaroo Valley, are smaller. As many of the festivals are in the regional areas, and as Australia is blessed with sunshine, camping is an important feature. Festivals are staged all year round. Folk clubs still operate in capital cities and some larger rural areas, so there is a loose network for touring artists. Several internationally renowned concertina players tour regularly, including Brian Peters and Noel Hill.

The website http://www.bushtraditions.org/links/linkfest.htm lists some of the main folk festivals including Australian folk music.

The National Library of Australia has an Oral History and Folklore Section which contains many field recordings of traditional concertina players. They offer a Folk Fellowship each year, and in 2016 the concertina player and collector Chris Sullivan was awarded the fellowship, allowing him to study the various recordings and to offer an academic overview. Sullivan presented his findings at a library lecture and a workshop at that year’s National Folk Festival.

DANCE

Dance plays a role in the concertina’s Australian life, and there are several clubs dedicated to Morris and to social dance. Many have concertina players. Here are several:

http://www.bushtraditions.org/: ‘Fostering interest in, knowledge about, and enjoyment of, Australia’s cultural heritage of music, dance, poetry and folklore’.

http://www.colonialdance.com.au/: Heather Clarke’s extensive site for dance steps, history, and music.

http://www.bushmusic.org.au/: The Bush Music Club, based in Sydney, is the oldest folk club in Australia and, arguably, one of the oldest folk clubs in the world. It has been actively promoting Australian folk traditions for over 60 years and will continue to do so well into the future

http://www.bendigobushdance.org.au: The Bush Dance and Music Club of Bendigo website offers a large number of videos of traditional and social dances from Australia.

One of the important contributors to the continuation of the concertina in Australian dance has been the community of Nariel Creek, a Victorian regional town. The Klippel family has been at the forefront of keeping this musical tradition alive. In 1973 I persuaded our national broadcaster, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, to film a documentary of the annual dance festival. The one – hour film centres on Con Klippel, a concertina player and driving force in the festival. You can read about the Klippel family and the festival at: http://www.vfmc.org.au/Nariel.htm.

COMMUNICATION CHANNELS

The main communication line for Australian concertina players is the ‘Concertina Convergence’, which can be contacted at concertinas@humphhall.org. The Concertina Convergence was established in August, 2015, as an email link between players, makers and repairers. The main purpose of the list of contacts is to give players opportunities to congregate and learn from each other. It also shares information such as where to find a repairer or where to acquire a concertina (new or old), and supports those who wish to build expertise in building and repair, by at least sharing information on who and where they are. The Concertina Convergence also arranges informal gatherings.

The two main gatherings of concertina players are the Concertina Convergence at the National Folk Festival staged at Canberra every Easter and the Bush Traditions gathering staged in Goulburn (New South Wales) every September for a Labour Day-long weekend.

TUNE COLLECTIONS AND AUDIO FILES

http://bushtraditions.wiki/: An extensive archive of Australian tunes, ABC files.

Peter Ellis and Harry Gardiner Collection. Published (free) by the Victorian Folk Music Club:

http://www.vfmc.org.au/FiresideFiddlers/MMMS2Size28MB.pdf.

Another resource for Australian concertina music is Dan Worrall’s House Dance CD Rom, which contains about 200 old time concertina recordings, nearly half of which are from Australia. It is sold at the Australian National Library’s online shop: https://www.nla.gov.au, and at Musical Traditions in the UK: http://www.mtrecords.co.uk/index2.htm, with profits going to the EFDSS.

(Editor’s Note: See elsewhere in this Journal for a full-text posting of this CD Rom.)

TUITION

There are several folk music tuition weekend festivals where the concertina is sometimes featured. The National Folk Festival has a four-day folk school prior to the commencement of the main festival program. These schools often include concertina workshop courses led by visiting artists.

The New South Wales English player Steve Wilson refers to his performance persona as ‘The Concertina Man’. He has a series of concertina tuition videos on You Tube: http://www.concertinaman.net/tutorials.html.

CONCERTINA HISTORY IN AUSTRALIA

The three main sources for history of the concertina in Australia are:

The Anglo-German Concertina: A Social History, Volume 2:

https://books.google.com.au/books?isbn=0982599617.

Dan Worrall’s extensive and impressive history of the Anglo.

http://www.bushtraditions.org/tutors/concertina.htm: This is a site primarily for players, and includes history, tuition, a list of tunes (in row, cross row and three-row varieties) and some exercises. The site is designed for what we call ‘bush music’.

http://www.warrenfahey.com.au/enter-the-collection/the-collection-m-z/musical-instruments-in-the-australian-tradition/: This site includes a history of the concertina and melodeon in Australia, information on Salvation Army Bands, and a Concertina Gallery.

SQUEEZERS

In preparation for this newsletter and overview, I sent an email to the Concertina Convergence mailing list attempting a guesstimate of the number of current players. Player and sometimes repairer Malcolm Clapp responded: ‘My guesstimate of concertina “owners” in Australia, who can play at least a little, would be into the low hundreds; if I had to put a number on it, probably somewhere between 200 and 300. Probably more than hurdy-gurdy players, but certainly less than accordion or banjo players, and far, far fewer than ukulele or harmonica players’.

Personally, I would suggest a higher number of around 600-800 ‘active’ and ‘sometime’ players – this out of a population of near 24 million persons in the country as a whole. The majority appear to be Anglo players, particularly of Celtic music. Opportunities to play have diminished somewhat in recent years. The National Folk Festival remains the best event for ‘concertina sightings’, where some of the older players, like Dave de Hugard and Dave Moss, can be heard. There are regular ‘sessions’ across Australia and particularly in Victoria:

http://irishsession.net/wordpress/traditional-irish-sessions-in-victoria-jan2010/

A recent email discussion among members of the Concertina Convergence tossed around the idea of introducing the instrument to young players through a school-run instrument lending program, supported by members who would demonstrate and mentor.

SQUEEZED OUT AND SADLY MISSED

Two of Australia’s favourite concertina players recently passed away.

Peter Ellis (1946-2015), Anglo player, expert dance accompanist, and prime mover in the Bendigo Bush Dance movement, left a legacy of books, tune collections and videos. He was honoured in 2012 with the Order of Australia for ‘service to the arts through the collection and preservation of Australian folk history and heritage’. Here is a video of Peter Ellis playing a march/waltz learnt from the Guildford Orchestra:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNAU9Yk9njM .

Here is a complete list of videos featuring Peter Ellis: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL1sxNfGXQ05jAwcViG6a4KTiTKkxI4hAN

Danny Spooner (1936-2017) passed away earlier this year. He was internationally recognised as a singer and English concertina player. He had an extremely large repertoire of songs, and was a regular fixture at festivals. The 2017 National Folk Festival staged a tribute concert in his memory. Danny’s concertina style was mainly block chords, which he used to great effect as accompaniment to his singing. Danny leaves behind a large catalogue of recordings which can be seen at http://www.dannyspooner.com.

Here is Danny Spooner singing Lovely Nancy (with English concertina), recorded by Rob Willis at the National Library of Australia, 25 May 2016: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gFISiZWGQRI.