Henrik A. Müller

Introduction

A few years after buying an English concertina in 1976 and commencing to play Irish folk music on it, I was introduced to an LP titled Noel Hill and Tony Linnane. 1 It confirmed a suspicion that I had tried to ignore: that the concertina used in Ireland was the Anglo, a system I didn’t dare attempt to learn without a teacher. By 2002, frustrated with my playing and close to giving up, I went to the Scandinavian Squeeze-In in Torna Hällestad (outside Lund), close to where I live in southern Sweden. Someone had brought a Stagi miniature (18B) English concertina; and to my surprise, I found it both easier to play and just as musically capable as my 1909 Wheatstone (#24994). One month later I had an importer-friend of mine buy one for me. I removed the thumb strap and the finger rest, added wooden sections to make it feel like a 6 ¼-inch instrument, as well as hand rails and Anglo-like hand straps, and was then hit by a new sense of frustration: I wanted an instrument like this one, but of better quality and with more notes.

Unfortunately, such an instrument didn’t exist. And thus there was the question: should I have one made for me or should I make one myself? Given my practical background, I chose the latter course, and in 2006, a 27-key, accordion-reed instrument was ready. I then went to Ireland, to the epicenter of Irish concertina playing at the time: “Éigse Mrs. Crotty”, in Kilrush, County Clare. Twelve years, a few refinements, and approximately 5,500 playing-hours later, I am now playing a concertina that is a mix of old and new: it has end boxes of my own design, replacing those of the 1909 Wheatstone. The following describes the process from idea to finished instrument.

The Stagi miniature

Having encountered the Stagi miniature at the Scandinavian Squeeze-In in 2002, I bought one with the intention of investigating why it worked so well. Yet when it arrived, it did not look at all like the photo on the company’s site: the metal finger rests were gone, replaced by leather straps like that for the thumb, thus making it virtually unplayable (at least for me). Since, however, I intended to remove whatever straps and finger rests there were anyway, this did not present a major problem. Over the years, a combination of instinct and experiment had made me aware of the limiting influence of tying down finger 4 in the finger rest, just as Göran Rahm has recently described in an article about the use of the fourth finger on the English concertina. 2 That and the painful pull in my thumb joints whenever I attempted more dynamic playing was incentive enough for wanting a change.

Studying the Stagi quickly revealed two reasons for its enhanced playability:

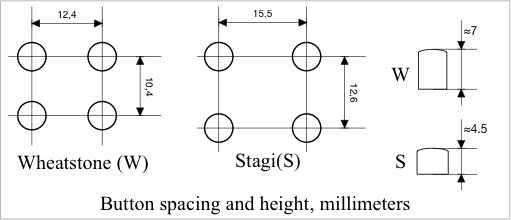

(1) Compared to the Wheatstone, there was more room for the fingers (Fig. 1).

(2) The buttons went all the way down, flush with the end plates—I call them “deep buttons”—something that felt very pleasant (and stood in contrast to most concertinas, where they stop approximately halfway down). And since they were also shorter than the Wheatstone buttons: 4.5 mm vs. 7 mm, this also provided a feeling of having “more room”. Finally, that the Stagi buttons were slightly larger in diameter: 5.5 mm vs. 5 mm, seemed to make no difference.

Modifying the Stagi

Since I wanted to try an Anglo-like strap with hand rails, the first thing that I had to do was make the Stagi miniature bigger, “camouflaging” it as a 6¼-inch instrument by adding a new lower and larger piece, where the straps and hand rails could be placed. Moreover, I angled these at approximately 15 degrees (not straight across as on an Anglo) in order to more easily reach the lowest buttons. Lastly, I realized that a thumb strap would be necessary, since the small Stagi bellows would collapse at the pull from the new, larger part. Several hand straps and a pair of thumb straps later, I had a proof-of-concept instrument (Fig. 2).

Playing was now a pleasure! The instrument was considerably lighter, and the painful pull in my thumbs was gone, transferred to the angled hand straps. As for the thumb straps, they were mainly for stabilization.

A serious decision

After a month of playing, it slowly dawned on me that I very much wanted such an instrument, but with more notes and with an upgrade in quality. Again, the problem was that such an instrument did not exist, which meant that either I had to have it made (if I could describe it sufficiently well) or make it myself. And once again I decided to make it myself, with the characteristics described above, which I call the “essential features”.

I started constructing the instrument in August 2005 and finished it in late April/May 2006 (the process is documented in detail on my web site). 3 The result was a 27-key, 7F, accordion-reed concertina (Fig 3) that had thumb straps (I didn’t dare omit them). These were designed so that the thumbs would go in as far as possible, and they were just wide enough to let me bend my thumb inside them.

Off with the thumb straps

In mid-August 2006, I attended “Éigse Mrs. Crotty”, and on my return I started to play in local (Swedish and Danish) sessions. During the summer of 2007, I began to wonder about the thumb straps; they were, after all, nothing more than a carry-over from the little Stagi with its small bellows. It was easy enough to test the instrument without them: I removed the thumb screws that held the straps and held my breath – nothing happened except that there was a feeling of greater freedom. After playing without the thumb straps for one week, I removed them completely, made a new set of hand straps, and used the old thumb screws to hold these in place (Fig. 4).

The essential features and their effect on playing

The essential features effect the way one plays in three ways:

(1) Button spacing: I have always thought that the English concertina’s cluster of buttons was too crowded, too many buttons in too small an area. Thus it is no surprise that the combination of shorter buttons and more space between them reduces the risk of “getting caught in the buttons”. It also allows for more creative, unorthodox fingering.

(2) Button travel/deep buttons: having shorter buttons that depress all the way, flush with the end plate, had more impact than I could have expected. Traditional Irish music has a lot of repeated notes, and to preserve the flow of the tune, they need to be performed by switching fingers; deep buttons go a long way in facilitating this.

(3) Angled hand straps: while the 15-degree angle is necessary in order to reach the low notes, the straps themselves permit full control of volume, right down to the volume envelope of a single note. A suitable analogy is to think of the hand straps and bellows as a fiddler’s bow. 4

Finally—though not technically an “essential feature”—I left out the sharps and flats that I didn’t need; and my latest instrument lacks seven of these. This is a personal preference, and nothing prevents the construction of an instrument with all the sharps and flats in place.

Conclusion

Today (2018), I play a mix of old and new: my 1909 Wheatstone with its pair of new end boxes (Fig. 5).

To my way of thinking, this “hybrid” brings out the best of the Wheatstone reeds. Owing to the degree of control and freedom of the fingers that the instrument affords, the reeds have greater dynamic range and brilliance than they did inside the original instrument. It is the culmination of more than ten years of intensive playing, discovery, and adjustments.

Finally, at the time of writing (Fall 2018), the Lancashire concertina maker Alex Holden has just finished a set of replacement end boxes that he made for a client’s 1914 Wheatstone Model 21 precisely to my specifications (Fig. 6), while another set is in the works.

- Tara Music, TACD 2006 (1978). Tony Linnane was a fiddler.

- “The English Concertina and the Dilemma of the Fourth Finger: An Ergonomic View”, The Concertina Journal, “articles”, no. 4 (September 2028), online at https://www. concertinajournal.org/articles/the-english-concertina-and-the-dilemma-of-the-fourth-finger.

- “Concertina Matters”, online at www.concertinamatters.se.

- For a contrary point of view, see Allan Atlas, Contemplating the Concertina: An Historically-Informed Tutor for the English Concertina (Amherst: The Button Box, 2003), 27-32, who calls it a “somewhat false analogy”.